May 2023 Cutting Edge Newsletter

Jump to The Whole Surgeon

Jump to Multi-Institutional Trials Committee

Jump to Multi-Institutional Trials Sub-Committee

Jump to Acute Care Surgery Committee

Jump to Palliative Care Committee

Jump to DEI Committee

Jump to Prevention Committee

Jump to Pediatric Trauma Committee

Jump to TSACO

Editor’s Letter

Written by: Shannon Marie Foster, MD, FACS

Friends and Colleagues –

The spring is upon us and I hope it finds you well and thriving. Of course, there are challenges: the weather is fickle and unpredictable; we are surrounded by a constant barrage of inter-personal and gun violence; and funding, reimbursement, and staffing issues in all systems and demographics are leading to ever-more frustrations and burn-out. Yet, as always, there is beauty and hope: April brought the official declaration to end the COVID national emergency and associated mandated public health measures; the rain arrived in California as did statewide legislation to support bleeding control efforts (thanks in part to the dedicated leadership of AAST members Amy Liepert and Jay Doucet); and the match and filling of surgical residency and fellowship positions demonstrates that our pipeline remains full.

As we have previously teased, you will notice the continued changes of the Cutting Edge quarterly newsletter – all intended to bring the full scope of the activities and reach of the AAST directly to you in one readable format. In the email page and scroll, note the opening list of the most important looming dates, the bottom inclusion of the most read/most impactful current JTACS articles as open access (free for all readers!), and a series of efforts to increase the sense of camaraderie and shared experiences of our members. Photos and duration in AAST will accompany each author (is your profile up to date?), images from AAST activities will be scattered throughout (send some to us!), and perhaps my favorite addition - the inclusion of The Whole Surgeon: Get to Know Your AAST where members have shared personal stories about life outside of work.

While I am constantly grateful for the work and leadership of each of you, I am not alone in the regular underpinnings felt of arms-length awe and imposter syndrome accomplishment can cause. These efforts and changes to our publication are intended to break down barriers and build community and camaraderie. We are each more than job titles and publications – we are friends and family and humans who need rest and respite and fun, full of unique interests and talents and ideas. When embraced, those personal elements propel and shape our motivation, ambition, and successes in the science and skills of our surgical career.

Feedback, comments, questions, and participation always welcome…

[email protected] or [email protected]

SMF

Get to Know Your AAST Colleague

The Whole Surgeon

Multi-Institutional Trials Committee

AAST Multicenter Trials Committee Update

Written by: Joseph DuBose, MD

The AAST MCT continues to review and support the implementation of high-quality multicenter research efforts designed and led by our membership. Several great efforts are being developed that are open to enrollment and support from fellow AAST members. In this newsletter, we highlight one specific effort we hope you will consider contributing to.

A multi-institutional, retrospective review for validation of the cirrhosis outcomes score in trauma (COST):

Liver disease affects one out of every 10 people in the United States. This number is likely underestimated as many cases of liver disease, particularly compensated cirrhosis, go undiagnosed. In 1990, cirrhosis was identified as an independent predictor of poor outcomes in trauma patients. However, current trauma injury grading systems, such as injury severity scores (ISS) and trauma injury severity score (TRISS), do not take into account liver dysfunction as a risk factor. A score that includes the degree of liver dysfunction would enhance the ability of ISS or TRISS to predict mortality in trauma patients with cirrhosis. While the Child-Pugh (CTP) classification system was historically used to quantify the severity of liver dysfunction, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD – Tbili, Cr, INR, Na) score is now widely used as an index of liver disease severity, for survival prediction, for surgical risk stratification, and for prioritization of organ allocation. The MELD score is more readily available than the CTP score for the prediction of mortality in trauma patients. Several prior studies have investigated combining trauma injury grading systems with known liver dysfunction scales. Corneille et al found ISS + MELD and ISS + CTP were stronger predictors of mortality than ISS alone for both. Inaba et al found each unit increase in the MELD score was associated with an 18% increase in the odds of mortality, adjusted odds ratio 1.18.

In our pilot study, a total of 318 cirrhotic trauma patients were analyzed of which the majority were males who suffered blunt trauma. The primary outcome of mortality in-patient, 30-days, 60-days, 90-days, and 1-year was evaluated. COST which was defined as the simple sum of Age, ISS, and MELD was associated mortality on regression analysis, in increasing intervals. A regression analysis of the three individual variables did not demonstrate a need to weigh the components of the score. Adding the individual variables in a weighted fashion did not significantly improve the AUROC and it would add significant complexity to the score calculation. The primary aim of this MIT is to review the risk factors and outcomes of cirrhotic trauma patients to validate the proposed COST mortality prediction model created at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist. Secondary goals include elucidating the impact of cirrhosis on morbidities, hospital/ICU LOS, and ultimate patient disposition. Achieving the specific goals of this proposed trial will further our understanding for the prognosis of cirrhotic trauma patients and improve goals of care discussions with patients and their families.

If interested in participation in this study, please contact Dr. Rachel Appelbaum at [email protected]

AAST Survey Sub-Committee Update

The AAST Survey Sub-Committee was formed in January 2023 and has since assumed the task of reviewing and approving requests for surveys of our members. The sub-committee has made extensive revisions to the submission process, aiming at improving the quality of disseminated surveys, reducing survey fatigue, enhancing participation, and most importantly, improving the likelihood of acceptance of related manuscript in peer review journals.

The following are some of the new features:

- Submission process: Survey Proposals will now be completed using a revised online form that will allow the reviewers to better assess the quality of the proposed survey.

- Survey Design and Reporting: To uphold survey standards and likelihood of peer-reviewed publication, we now require that surveys are designed in keeping with the EQUATOR CHERRIES Checklist. The submissions system has been designed with this in mind. The CHERRIES Checklist is open access and can be found here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15471760/

- Submission Deadlines: Ten survey applications are accepted each quarter, considered in a first-come first-serve basis. The deadlines for quarterly review are the 15th of January/April/July/October. Surveys submitted outside of the first 10 applications will be rolled over to the next quarter. Survey authors will be updated on the status of their submission.

- Survey Review and Selection Process: To minimize survey fatigue, we aim to circulate 1 survey each quarter, but will allow for up to 6 surveys annually, including AAST committees-initiated ones. All submitted survey applications will be reviewed using a standardized scoring process by the Surveys Sub-committee. The top scoring survey will be selected for dissemination. Surveys not selected in a given quarter may be 1) held for publication the following cycle, 2) returned for revision, or 3) declined. Authors will be updated on the status of their survey with feedback.

- Survey Dissemination Timeline: Selected surveys will be published during the corresponding quarter on the first Monday of March/June/September/December. The survey request will be delivered to our members twice in separate emails and will be included in the weekly and monthly AAST newsletters. They will also be available on the AAST website for the duration that was requested by the investigator(s).

We remain highly committed to supporting our members with their research endeavors. The sub-committee is currently working closely with AAST staff on solutions to further enhance participation of our membership in these surveys. A few distinct opportunities have been identified as we continue to work towards this goal.

Acute Care Surgery Committee

Early Nutrition Support Intervention Positively Affects Postoperative Outcomes

Written by: Sara Bliss PharmD, Suresh Agarwal MD, Paul Wischmeyer MD, Krista Haines DO

Take Away Points:

- Do nutrition assessments regularly because surgery and trauma patients fall well below nutritional targets, and malnutrition diagnoses are frequently missed

- Start nutrition early and consider pre-operative optimization if time allows

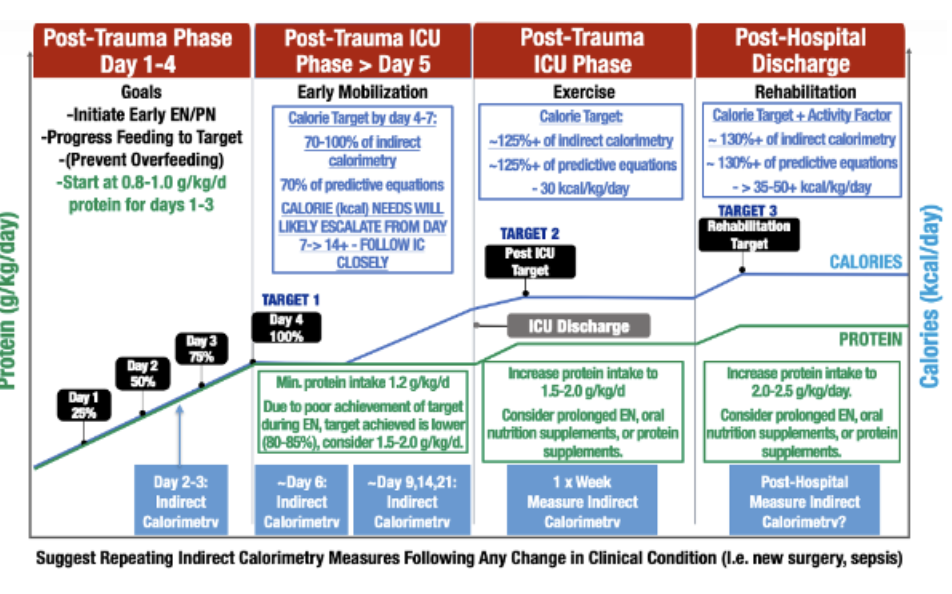

- All patients are different, and their protein and calorie goals are dynamic, changing over time. Consider a personal approach using regular indirect calorimetry as both over and underfeeding lead to poor outcomes.

Malnutrition is a common, underdiagnosed, comorbidity among surgical patients. Depending on the criteria used to define malnutrition, prevalence is reported as high as 50%1 and is especially common among elderly patients (> 60 years old). Malnutrition is also associated with chronic inflammation resulting in sarcopenia and decreased muscle strength. Likewise, both traumatic injury and surgical intervention activate inflammatory pathways. Coupled together, these processes have deleterious effects on postoperative outcomes, including the worsened risk of infections, amplified problems with wound healing, compounded hospital- and ICU-length of stay (LOS), and increased mortality. These complications result in increased hospital resource utilization and cost to the health system. In spite of the high prevalence and known deleterious effects on outcomes, early and appropriate nutrition interventions remain low in hospitalized patients, in both those admitted for elective and emergent surgeries.2

Given the significant risk of malnutrition in acute care surgery and critically ill (ICU) patients, nutrition intervention should be considered a cornerstone of care and recovery. Two organizations have developed and published guidelines that address perioperative feeding best practices: the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society. ESPEN recommendations include nutrition assessment and evaluation of nutrition status both pre- and post-operatively; perioperative nutrition support in patients diagnosed with malnutrition or those determined to be at nutritional risk; and optimization of perioperative nutrient delivery in patients without risk of aspiration. Perioperative nutrition support should be provided via the oral, enteral (tube feeding), or, if unable, parenteral route depending on the functional status of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the amount of volitional intake the patient tolerates. For patients with severe malnutrition, 7 to 14 days of preoperative nutrition support via an appropriate route is preferred if surgery can be delayed. Malnourished patients undergoing major surgery benefit from perioperative immune-modulating formulas (arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and ribonucleotides) from an infectious risk standpoint.3 The ERAS Society originally published perioperative bundle care guidelines specific to colorectal surgery but has since been adapted for various surgical subspecialties. Similar to ESPEN, minimization of perioperative fasting as well as identification and treatment of malnutrition are key components. The ERAS guidelines reiterate the recommendation for immunonutrition. 4

Applying nutrition guidelines to acute care and trauma patients

Due to improved trauma, surgical, and ICU care, severe abdominal trauma victims are surviving their injuries at higher rates than ever before6,7. Unfortunately, extensive evidence demonstrates that trauma victims experience significant post-hospital impairments in physical function, muscle wasting/weakness, poor quality of life (QoL), and delayed return to work8-10. These impairments, more commonly termed ICU-Acquired Weakness (ICU-AW), burden survivors and their caregivers for months to years following injury8.

The catabolic state induced by trauma and critical illness is a significant driver of ICU-AW12. At this stage, personalized nutrition therapy is an essential component of metabolic support to support vital organ system functions, preserve muscle mass, and allow recovery and wound healing while the underlying injury is treated13. In patients with a functional gastrointestinal (GI) tract, oral nutrition supplements are paramount to prevent or treat malnutrition. As recommended by the ERAS guidelines, a focus on the minimization of fasting and early oral intake must be considered. Early, oral nutrition has numerous benefits including decreased length of stay and decreased infectious complicaitons..14 In mechanically ventilated ICU patients for whom volitional intake is not possible but GI function remains intact, initiation of early enteral nutrition should occur regardless of baseline nutritional status.15

What about Parenteral Nutrition?

In patients for whom oral or enteral nutrition is not appropriate, parenteral nutrition (PN) should be considered. Previously, PN was thought to increase the risk of infection due to early studies which used PN without consideration of GI function and without regard of total calorie intake from all sources. These early studies demonstrated an increased risk of infection in patients who did not meet the criteria for malnutrition, leading to a recommendation to withhold PN until at least day 7 of NPO status in patients who were well-nourished. More recent studies indicate that PN confers to greater infectious risk compared to standard of care in ICU patients.16-19 These data supporting the safety of PN use are likely due to increased knowledge of ideal glycemic targets improvements in infection control procedures and other improvements in supportive care that have become ubiquitous. The results of these studies are reflected in the most recent American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) guidelines for nutritional support of the ICU patient, which stipulate that there is no preference for PN vs. EN in critically ill patients, making either an acceptable choice.15

A review of current practice reveals <50% of prescribed nutritional goals are delivered to ICU patients, even in malnourished patients20, with surgery and trauma patients often being fed most poorly and achieving only 33% of nutrition needs for the first two weeks in ICU 21. Unfortunately, U.S. ICUs demonstrate the most inadequate nutrition delivery compared to other world regions20. There is some conflicting evidence on the timing of PN in critically ill patients. Early studies attempting PN within 7 days of admission showed no significant difference in outcomes. More recent data suggests patients with early (within 3 days) PN suffered from less nosocomial infections..22.23

A Personalized Approach

Minimal research has incorporated a personalized approach to nutrition. Furthermore, none of these trials evaluated major traumatic injuries, and few have examined early nutrition on recovery of physical function, muscle mass, or QoL. It is essential to provide personalized nutrition support to vital organs, preserve muscle mass, and enhance recovery and wound healing while treating the underlying injury24,25. Guidance by serial objective, longitudinal indirect calorimetry (IC) measurements in critically ill and non-critically ill surgical patients with severe abdominal injuries may be the solution to addressing nutritional needs in this variable population. Energy expenditure (EE) in trauma and ICU patients is highly variable, changes daily, and is complicated by initial injury/illness, severity of disease, nutritional status, and medical treatment26-29. However, estimating patients' caloric needs is challenging due to the complex dynamic metabolic alterations observed in critical illness 26. Studies have shown that predictive formulas to calculate EE in ICU patients are inaccurate26. Tissue injury accompanying major trauma further complicate estimation of calorie and protein requirements.26,28,29. For these reasons, much of the research investigating early nutritional pathways cannot be extrapolated to major trauma.

Recent ICU nutrition guidelines recommend IC as a mechanism to precisely determine caloric needs, recommendations summarized in Figure1.30,31 Metabolic cart data (i.e. IC) to optimize nutritional support has been associated with improved clinical outcomes18,32. Unfortunately, recent studies have shown current commercially available IC’s are often inaccurate 33,34 and the inconveniences and challenges of routine ICU IC measurements (i.e., complex maintenance, challenging calibration, long warm-up duration, large device size, and limitation of Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (FiO2) etc.) have led to significant challenges to routine IC use and inability to routinely utilize in trauma/ICU practice35,26. However, newer devices are available for practical, easy use in ICU patients. Characteristics of more recent machines will allow for expanded use of IC to optimize nutritional support prescription by limiting the risk of under or overfeeding, which are both known to lead to adverse clinical and physical function outcomes. 28

Trials continue to emerge demonstrating the importance of nutrition as related to clinical outcomes in surgical patients. Early nutrition support via an appropriate route positively impacts clinical outcomes. Newer models of the gold-standard indirect calorimetry machines may demystify the nutritional needs of complex, dynamic patients in multiple settings.

References

- Bruun L, Bosaeus I, Bergstad L, Nygaard K. Prevalence of malnutrition in surgical patients: evaluation of nutritional support and documentation. Clinical Nutrition. 1999;18(3):141-147.

- Martínez-Ortega AJ, Piñar-Gutiérrez A, Serrano-Aguayo P, et al. Perioperative Nutritional Support: A Review of Current Literature. Nutrients. 2022;14(8):1601.

- Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clinical Nutrition. 2021;40(7):4745-4761.

- Gustafsson U, Scott M, Schwenk W, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Clinical nutrition. 2012;31(6):783-800.

- Wischmeyer PE, Carli F, Evans DC, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Nutrition Screening and Therapy Within a Surgical Enhanced Recovery Pathway. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(6):1883-1895.

- Smith IM, Beech ZK, Lundy JB, Bowley DM. A prospective observational study of abdominal injury management in contemporary military operations: damage control laparotomy is associated with high survivability and low rates of fecal diversion. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):765-773.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Dunn JC, Bader JO, Belmont PJ, Jr. The nature and extent of war injuries sustained by combat specialty personnel killed and wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, 2003-2011. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(2):287-291.

- Maley JH, Brewster I, Mayoral I, et al. Resilience in Survivors of Critical Illness in the Context of the Survivors' Experience and Recovery. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1351-1360.

- Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683-693.

- Laughlin MD, Belmont PJ, Jr., Lanier PJ, Bader JO, Waterman BR, Schoenfeld AJ. Occupational outcomes following combat-related gunshot injury: Cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;48:286-290.

- Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1308-1316.

- Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015;19:35.

- Jensen GL, Wheeler D. A new approach to defining and diagnosing malnutrition in adult critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18(2):206-211.

- Williams DG, Ohnuma T, Haines KL, et al. Association between early postoperative nutritional supplement utilisation and length of stay in malnourished hip fracture patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2021;126(3):730-737.

- Compher C, Bingham AL, McCall M, et al. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2022;46(1):12-41.

- Doig GS, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, et al. Early parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients with short-term relative contraindications to early enteral nutrition: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2013;309(20):2130-2138.

- Harvey SE, Parrott F, Harrison DA, et al. Trial of the route of early nutritional support in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1673-1684.

- Heidegger CP, Berger MM, Graf S, et al. Optimisation of energy provision with supplemental parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9864):385-393.

- Reignier J, Boisrame-Helms J, Brisard L, et al. Enteral versus parenteral early nutrition in ventilated adults with shock: a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label, parallel-group study (NUTRIREA-2). Lancet. 2018;391(10116):133-143.

- Cahill NE, Dhaliwal R, Day AG, Jiang X, Heyland DK. Nutrition therapy in the critical care setting: what is "best achievable" practice? An international multicenter observational study. Critical care medicine. 2010;38(2):395-401.

- Drover JW, Cahill NE, Kutsogiannis J, et al. Nutrition Therapy for the Critically Ill Surgical Patient: We Need To Do Better! Jpen-Parenter Enter. 2010;34(6):644-652.

- Wischmeyer PE, Hasselmann M, Kummerlen C, et al. A randomized trial of supplemental parenteral nutrition in underweight and overweight critically ill patients: the TOP-UP pilot trial. Critical care. 2017;21(1):1-14.

- Gao X, Liu Y, Zhang L, et al. Effect of early vs late supplemental parenteral nutrition in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA surgery. 2022;157(5):384-393.

- Wischmeyer PE, San-Millan I. Winning the war against ICU-acquired weakness: new innovations in nutrition and exercise physiology. Crit Care. 2015;19 Suppl 3:S6.

- Dijkink S, Meier K, Krijnen P, Yeh DD, Velmahos GC, Schipper IB. Malnutrition and its effects in severely injured trauma patients. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2020:1-12.

- Oshima T, Berger MM, De Waele E, et al. Indirect calorimetry in nutritional therapy. A position paper by the ICALIC study group. Clinical Nutrition. 2017;36(3):651-662.

- Wischmeyer PE. Nutrition Therapy in Sepsis. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34(1):107-125.

- Fraipont V, Preiser JC. Energy estimation and measurement in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(6):705-713.

- Guttormsen AB, Pichard C. Determining energy requirements in the ICU. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(2):171-176.

- Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):48-79.

- McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(2):159-211.

- McClave SA, Martindale RG, Rice TW, Heyland DK. Feeding the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(12):2600-2610.

- Sundstrom M, Tjader I, Rooyackers O, Wernerman J. Indirect calorimetry in mechanically ventilated patients. A systematic comparison of three instruments. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(1):118-121.

- Graf S, Karsegard VL, Viatte V, et al. Evaluation of three indirect calorimetry devices in mechanically ventilated patients: which device compares best with the Deltatrac II((R))? A prospective observational study. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(1):60-65.

- De Waele E, Spapen H, Honore PM, et al. Introducing a new generation indirect calorimeter for estimating energy requirements in adult intensive care unit patients: feasibility, practical considerations, and comparison with a mathematical equation. J Crit Care. 2013;28(5):884 e881-886.

- De Waele E, Jonckheer J, Wischmeyer P. Indirect calorimetry in critical illness: a new standard of care? Current opinion in critical care. 2021;27(4):334.

Figure 1: Personalized Indirect Calorimetry-Guided Trauma Nutrition Algorithm (derived from recent evidenced-based ICU nutrition reviews and adapted from Waele et.al.36) Please note: Suggested IC measurement days are intended as guidelines to create consistency in measurement throughout patient stay. Ideally, IC measurements should be performed 2-3 times/week and when there is a significant clinical change patient status, such as a new infection, sepsis episode, or increased physical activity/rehabilitation.

Palliative Care Committee

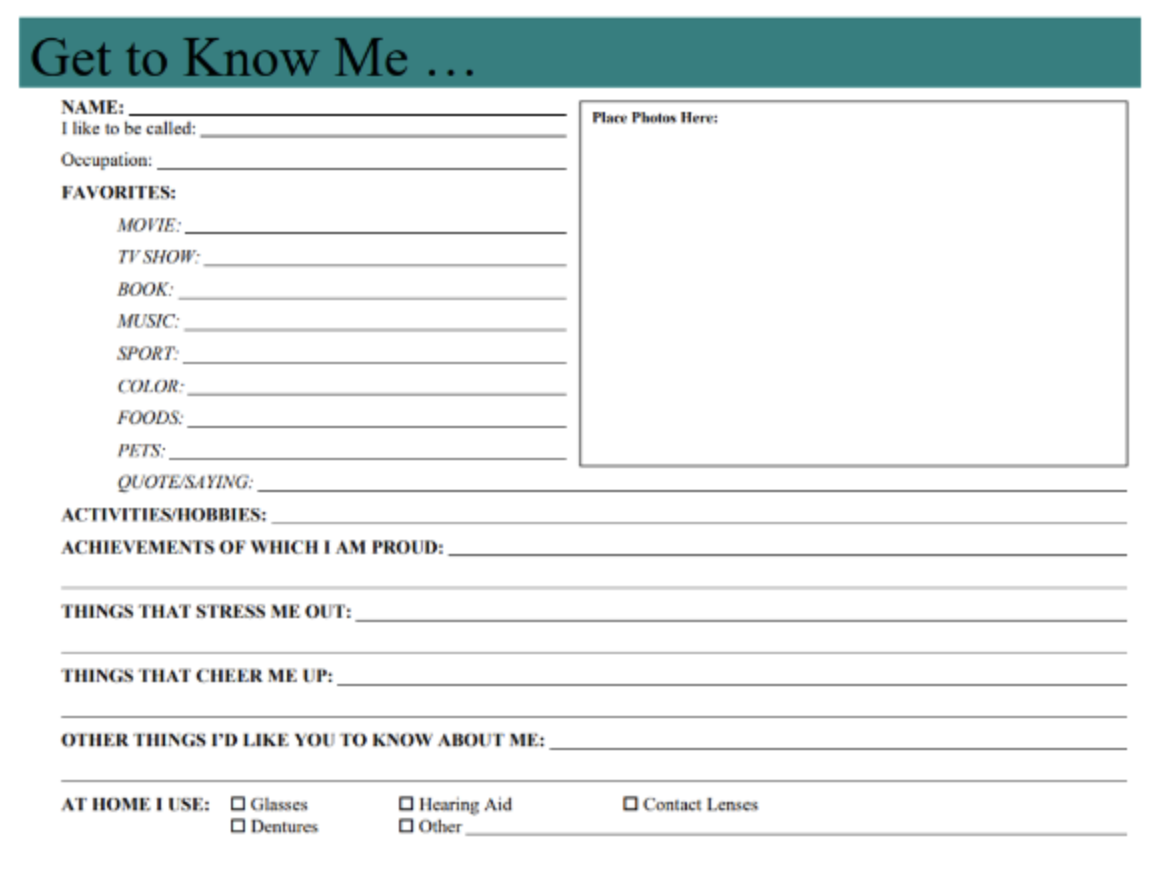

The “Get to Know Me” Poster: an impactful intervention to humanize the patient and staff experience

Written by: Sarah Cottrell-Cumber, DO

In the care of critically ill patients, surgeons and ICU clinicians need to attend not only to the immediate clinical demands, but also to the higher human needs of psychological, social, and spiritual needs. Understanding patients as human beings who have preferences, accomplishments, hopes, and fears is paramount to providing compassionate care and achieving goal concordant outcomes. This is not always the easiest goal to achieve when caring for a patient with polytrauma or critical illness. The ICU is intrusive and overwhelming with monitors, constant beeping sounds, and a steady stream of staff and providers. The “Get to Know Me” patient posters are significant for patient and family support, as well as helping staff mitigate burnout.

These posters were originally developed in 2003 by the Ethics in Clinical Practice Committee (2003) at Massachusetts General Hospital in the ICU1. The pilot program originated from Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care, which was a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, committed to facilitating and implementing long-term changes that impacted healthcare for patients and their families. The posters have now been adopted by a number of hospitals nationwide. They are typically 18 inches x 24 inches in size and are placed in patients' rooms soon after arrival. The poster includes the patient’s biographic details such as name, nickname, background, need for any aid devices, hobbies, favorite color/books/movies/foods. It also includes a space for personal photographs.

These posters were originally implemented in the ICU and would travel with the patient when they transferred to the acute care floor. Some literature has shown “Get to Know Me” posters or boards to be helpful in mitigating post-ICU syndrome, through the creation of effective and ongoing dialogue between patients, families, and ICU staff2. While these posters likely have the most impact in the ICU when patients are often unable to communicate for themselves, understanding the patient preferences is valuable for all patients admitted to the hospital.

As a general surgery resident and current palliative medicine fellow, I first learned of these posters when I began training at a new hospital this past year. I came face to face with one in the ICU. This poster was a brand-new concept to me and I had yet to interact with them at any prior institutions. Immediately I was struck by the simplicity of the intervention with such large potential for positive intervention. While reading the “Get to Know Me” posters adds time to daily tasks, I gain some peaceful precious moments where I am reminded of how human patients are. After a devastating trauma or critical illness, patients often don’t look or feel human. Even their family members at bedside are only partial reminders of the lives these patients led prior to our meeting them in the ICU. And then I look at pictures of their graduations, on vacation with loved ones, or with pets (my personal favorite photos). I learn we share the same taste in books and movies. It is easier to picture the fulfilling life they must have had prior to the trauma or illness that led to us meeting.

I can recall an impactful poster experience. A 20-year-old young man was recovering from a severe traumatic brain injury after a motor vehicle crash. He had been transferred from the ICU and was awaiting placement in a LTAC for continued recovery. On his poster, it listed his nickname “Turtle”. His parents shared that no one ever called him by his full name, only ever “Turtle”. It was after he was called “Turtle” that he purposefully turned his head to voice for the first time. While a seemingly insignificant detail, this changed the trajectory of his recovery.

Not only are these posters paramount to providing care to patients physical, mental, and spiritual health, they have demonstrated benefit in mitigating staff burnout. It has been shown that when staff view patients as human that they find their work to be more fulfilling. A comparative study investigated nursing care behaviors after the implementation of the “get to know me” poster3. This study determined that interventions which focus the attention on the person and emphasize patient-focused care enhanced nurse caring behaviors and strengthened the patient-nurse relationship. In a time with the challenges of the COVID pandemic and the increasing strains on healthcare access and deliver, staff burnout feels like it is at an all-time high. If a simple poster can relieve staff distress, promote strong patient-caregiver relationships, and focus on the person not the patient—that feels like a valuable investment.

Humanizing ICU patients using a simple “Get to Know Me” poster is a simple intervention to bridge staff and patient experiences. If these posters don’t exist yet in your institution, I charge you to be the pioneer to introduce them into the ICU. If these posters do exist, I encourage you to read them alongside family members and pause for a moment to recognize the patient for the full human being they are; that few minutes of connection is therapeutic for us as providers and the families.

References:

- Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. Merging cultures: palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 Suppl):S388-S393. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000237346.11218.42

- Blair KTA, Eccleston SD, Binder HM, McCarthy MS. Improving the Patient Experience by Implementing an ICU Diary for Those at Risk of Post-intensive Care Syndrome. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(1):4-9. doi:10.1177/2374373517692927

- Goncalves SA, Strong LL, Nelson M. Measuring Nurse Caring Behaviors in the Hospitalized Older Adult. J Nurs Adm. 2016;46(3):132-138. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000312

- Gajic O, Anderson BD. "Get to Know Me" Board. Crit Care Explor. 2019;1(8):e0030. Published 2019 Aug 1. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000030

- UW School of Medicine. Communication Tools. End of Life Care Research Programs. https://depts.washington.edu/eolcare/products/communication-tools/. Published 2023.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee

Parents for Peace At LAC+USC

Written by: Anaar Siletz, MD, PhD, Arquimedes Barrera, MS, and Damon Clark, MD

As trauma surgeons, we have all had the experience of telling a family that their loved one has died. Many of us feel that these difficult conversations require the same skill and attentive care as a complex surgery. Too often, we must end the conversation knowing that we have just added unbearable pain to a social situation that is already strained from socioeconomic inequality. When we complete a surgery, we deliver our patients to the expertise of perioperative care to begin the healing process. When we complete the delicate operation of breaking horrible news to a family, where is the safe space to begin healing? Although there are many ways to provide support, the following describes one of our support systems at LAC+USC for families who have lost loved ones to violence. We hope this piece may encourage those who have, or hope to have, similar services within their trauma center.

As a case manager in the trauma ICU at our busy urban level I trauma center, Arquimedes Barrera noticed the suffering of the families who lost children to violence. Seeing the agony of the parents reminded him of personal tragedy; in their faces, he saw the face of his mother after his brother was killed. He did what he could for them in the ICU, but the terrible reality was that there was no long term support for these families, many of whom were also facing severe economic hardship and discrimination.

In 2013, Mr. Barrera, who has a Master’s degree in Human Development, partnered with Dr. Damon Clark, trauma surgeon and Director of the LAC+USC Violence Intervention Program; to create a long-term support group for these families. The group is called Parents for Peace or Grupo Apoyo Padres por la Paz, and is free and accessible for all who have lost loved ones at LAC+USC. The goal of Parents for Peace is to provide emotional support by emphasizing solidarity, empathy, and compassion as well as for grieving families.

Parents for Peace meets every other week, and all family members are welcome to attend, with more than 50 people currently in regular attendance. Many of the participants do not speak English, so the meeting is primarily conducted in Spanish by Mr. Barrera and Dr. Clark.

Discussions are opened on loss, grief, and healing. Participants share stories with each other that are difficult for them to express outside of this setting. Mothers who have been long-term participants become supporters of mothers new to the group. Those who have experienced unspeakable suffering may speak and be understood. Through this group and affiliated social programs, families can also receive assistance with basic necessities such as “gift” cards for food, transportation, and financial assistance with utilities and rent.

Parents for Peace is one way of approaching the goal of total care of the trauma patient, their families, and their communities. It creates the sheltered space for healing that is so desperately needed after the loss of the loved one.

Prevention Committee

Trauma Survivors – Pleading Voices

Written by: Thomas K. Duncan, DO

In collaboration with Congress, May was launched as the National Trauma Awareness Month in 1988 by the American Trauma Society (ATS). The organization has advocated for a multitude of themed prevention programs and education for all ages over the past 35 years. This year’s theme is “Roadway Safety is No Accident,” which aligns with the United States (U.S.) Department of Transportation Roadway Safety Strategy. America is still facing increasing numbers of traffic related injuries and fatalities. In 2021 alone, 42,915 people died on our roads, which is the highest number recorded since 2007.1,2 This article will be focusing on trauma survivors regardless of mechanism of injury.

As clinicians caring for the injured patient, our goal is to heal and discharge without causing any further harm. The continuum of care is often truncated when the patient is discharged especially if there is no follow up provided to the trauma team. The importance of having stories told by trauma survivors is not a new concept but is being brought to the forefront in the trauma realm. The aspect of listening to sometimes unheard voices and implementing key suggestions based on experiences to improve care provided to our trauma population is a major shift in our world.

Most trauma patients do not want to believe they are a trauma survivor, but approximately 70% of U.S. adults have lived through at least one traumatic experience.3 Many trauma survivors have a low self-esteem, are harshly self-critical, and short on self-compassion. Oftentimes, they quickly believe there is something wrong with them, or they have done something erroneous to deserve the terrible event that happened in their world. Because trauma is usually associated with a physical component, those that suffer emotional distress without external injuries tend to minimize their suffering.4 Traditionally, clinicians in trauma surgery and emergency medicine view trauma from the lens of a motor vehicle, motorcycle, or other moving cycle crash; assault; fall; stabbing; gunshot; or any other acute physical injury. Alternatively, mental health clinicians regard trauma as an extremely disturbing and distressing experience. These varying perspectives may lead to fragmentation of care.5 Although there is no universal definition for trauma, health care is trending towards accepting the most commonly referenced definition from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” Triggers of trauma that are interlocked into important social determinants of health include, but are not limited to, childhood or elderly neglect; inequity accessing education; housing; proper nutrition; poverty and systemic racism; experiencing or observing emotional, physical, and sexual abuse; having a family member or friend with a mental health or substance abuse disorder; and experiencing or witnessing community violence or while serving in the military.6,7,8

It takes courage and authenticity to accept the trauma survivor title and embrace services that come along with it. Inclusion in a group of survivors emboldens one to take the next step to making a positive outlook with their diagnosis. In the same realm, hearing survivor stories spark encouragement in others to create a pathway of resilience as they work towards days-months-years of healing their broken bodies and minds.

The Trauma Survivors Network (TSN), a program of the ATS that works in concert with many other organizations within the Trauma Prevention Coalition (TPC) – of which the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) is represented, work cohesively to “combine the resources of major professional organizations addressing the acute healthcare needs of the injured, promote collaborative efforts and develop effective strategies in injury/violence prevention while minimizing redundant and duplicative activities.”1 The TSN is a “community of patients and survivors looking to connect with one another and rebuild their lives after a serious injury. The underlying goal of their resources and programs is to ensure the survivors of trauma a stable recovery and to connect those who share similar stories.”9 Hospitals that provide care for the injured patient can become a TSN facility. In so doing, quality of care is improved by providing training materials, peer support groups from volunteer trauma survivors, and navigation of future steps. ATS partners with the TSN in providing local and national advocacy. It is felt that involvement in such advocacy and bringing awareness of trauma survivors and enabling the community at large to be aware of injury/trauma as a public health issue like cancer and heart disease recognition will only change the perception of how it is viewed in the general lens. Improved patient satisfaction by offering several products to patients and family addresses “family information starvation” by explaining coping mechanisms and dealing with trauma in the first hours and days post-injury. Lastly, the TSN increases the opportunity for philanthropy to enhance programmatic availability to survivors.9

Recognition that trauma is not only born in the form of physical injuries is highlighted by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma by requiring mental health screening as a new addition in the Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient (Grey Book).10 Providing care for trauma survivors can come in multiple forms, e.g., trauma survivors program/clinic (highlighted by Dr. David Livingston in his presidential address at the 81st AAST scientific meeting in 2022), Hospital Based Violence Intervention Programs, Family Justice Centers, etc.

The importance of the above philosophies has been adopted and will be interwoven into core aspects of the upcoming Advanced Trauma Life Support 11th edition course by highlighting injury prevention, trauma-informed care, and palliative care concepts. Not only is it critical to handle life-threatening injuries upon arrival of patients in the trauma bay, it has also been acknowledged that participants of the course should begin thinking about ways and means of addressing preventable injuries, treating patients without bias, and utilizing palliative care concepts after the golden hour period has been controlled.11

By lending a listening ear to our trauma survivors, we can make a change in patients ultimate outlook on life by creating a mechanism of not retraumatizing or falsely criminalizing our clientele and maintaining the human touch expected of clinicians in the goal of treating patients without instilling further harm, as expected of us by taking the Hippocratic oath at graduation. In addition, we can instill those salient prevention principles at the appropriate time that may have caused a patient’s injury, highlighting the term “Trauma/Road Safety is No accident.”

References

- amtrauma.org (American Trauma Society). Accessed April 17, 2023.

- transportattion.gov (U.S. Department of Transportation). Accessed April 17, 2023.

- thenationalcouncil.org (National Council for Mental Wellbeing). Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Brickel RE, Trauma-Informed Care. Why It’s Important to Identify as a “Trauma Survivor.” Trauma; 2020 Jul.

- Dicker R, Thomas A, et al. Strategies for Trauma Centers to Address the Root Causes of Violence: Recommendations from the Improving Social Determinants to Attenuate Violence (ISAVE) Workgroup of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. J Am Coll Surg.2021 Sep;233(3).471-478.

- Duncan TK. Trauma-informed Care. The Changing Dynamic of Health Care. AAST Cutting Edge. 2022 Nov.

- Menschner C, Maul A, Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation. ISSUE BRIEF. Advancing Trauma-Informed Care. Center for Health Care Strategies. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2016 Apr;1-12.

- SAMHSA (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. Available at:

http://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884. - traumasurvivorsnetwork.org (Trauma Survivors Network). Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Resources for the Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. 2022 Standards. Released March 2022.

- ACS COT ATLS 11th edition Committee

Pediatric Trauma Committee

Screening Guidelines for Venous Thromboembolism in the Pediatric Trauma Patient

Written by: Robert W. Letton, Jr. MD

INCIDENCE

Incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the pediatric trauma population can be upwards of 6%. It is extremely rare in patients less than 9 years of age, unless there are other contributing factors such as family history or central lines.

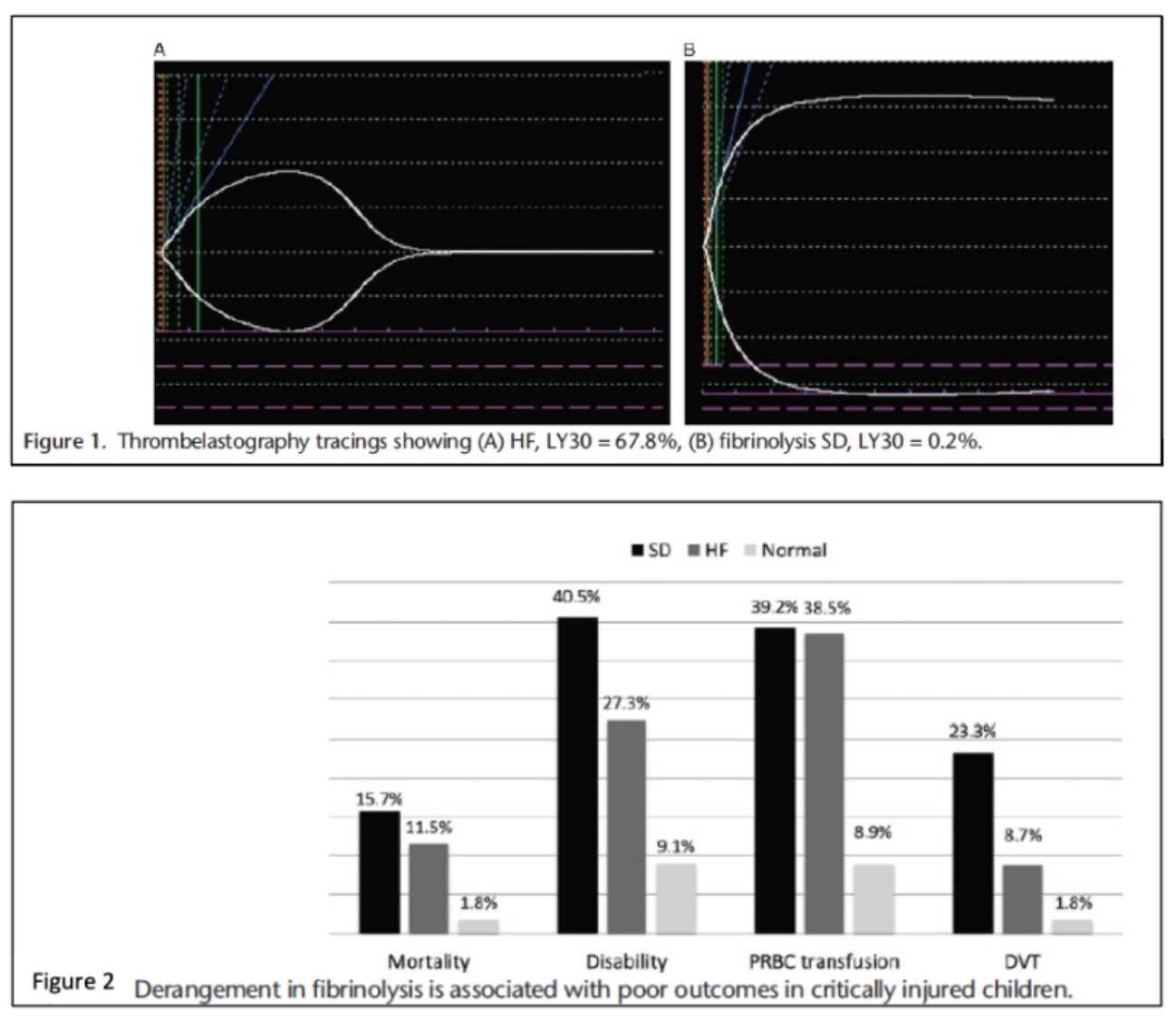

SCREENING

There is evidence that pediatric trauma patients with fibrinolysis shut down on TEG may be at risk for VTE (Figures 1 and 2).1

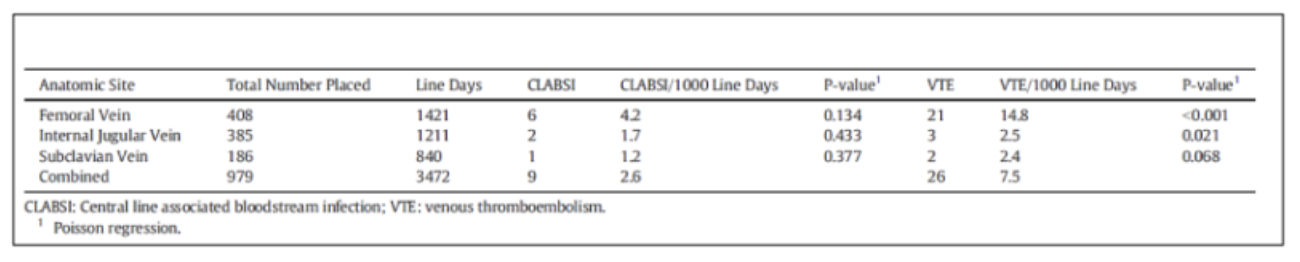

Other risk factors that contribute to VTE in the pediatric trauma population include central venous catheters, especially those in the femoral position (Table 1).2

Table 1: Percutaneous central venous catheter-associated CLABSI and VTE by anatomic site.

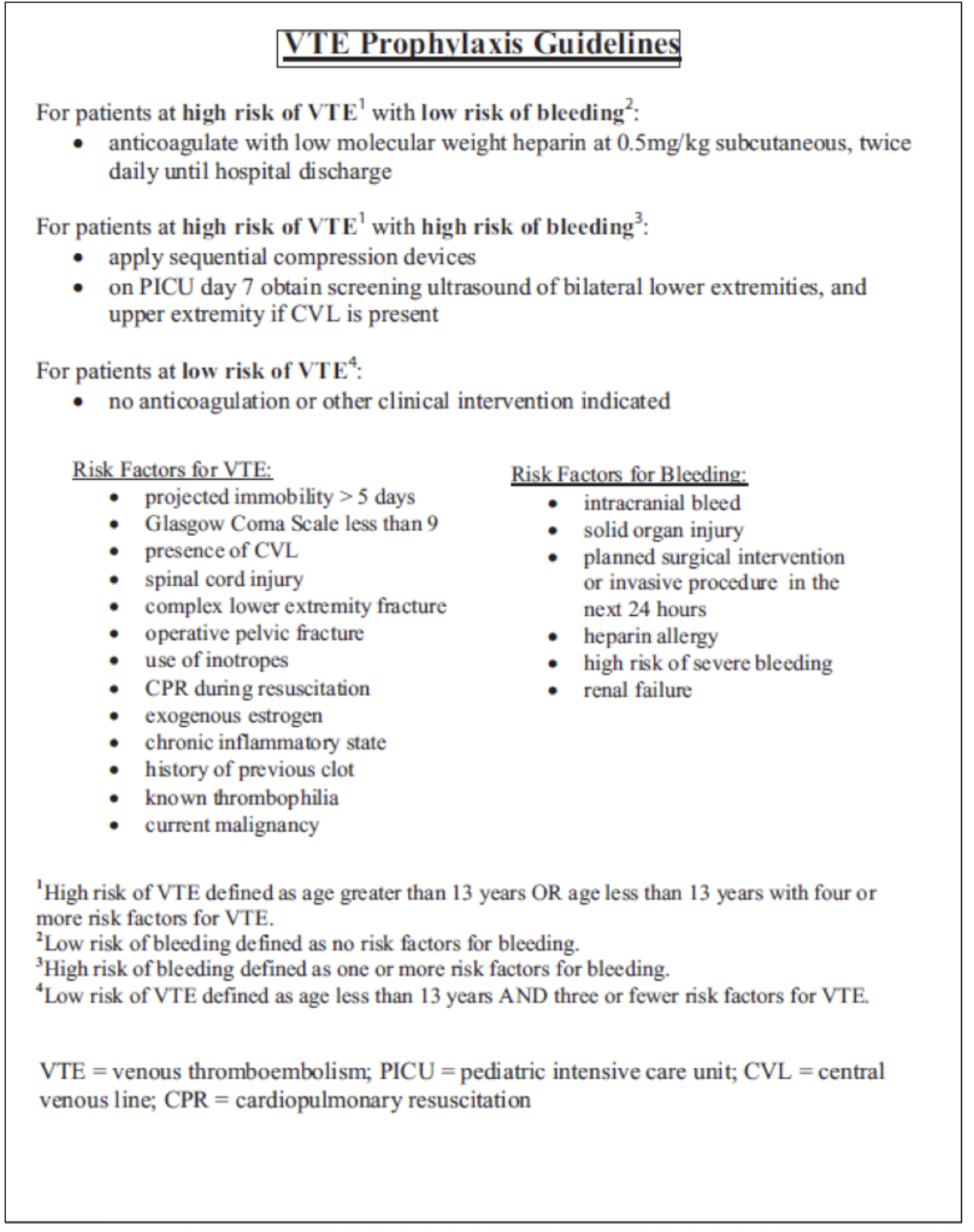

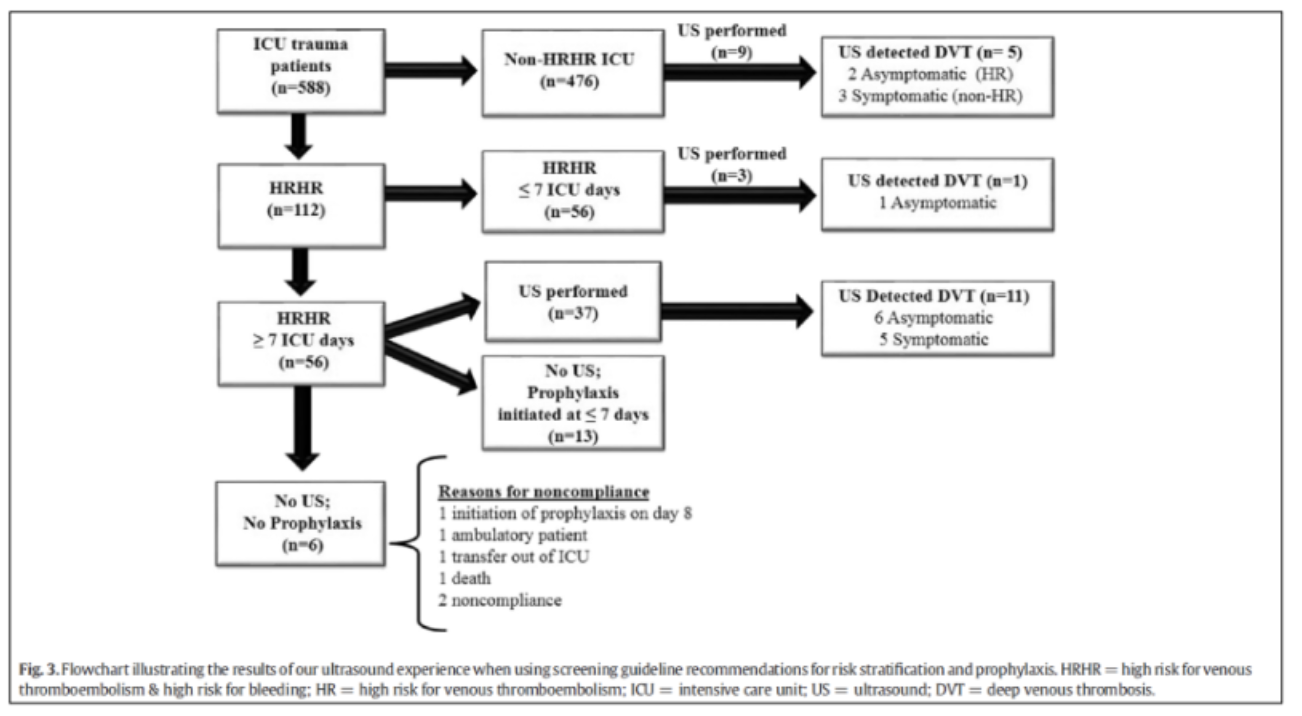

Numerous screening guidelines have been developed in many trauma centers. One relatively simple guideline was developed at the University of Wisconsin after noting a 6% incidence of VTE in their pediatric trauma population. They prospectively developed a list of risk factors (Figure 3).3 A key step for the high risk patients that are unable to be anticoagulated is obtaining a screening duplex ultrasound on the seventh day in the intensive care unit. This group considered age 13 years as the cut-off for high risk for VTE. Their guideline was validated this prospectively (Figure 4).4

Figure 3

Figure 4

The same group has also looked at screening in high-risk patients for VTE as well as bleeding. Although the incidence was low in the overall population, in those that were high risk, US screening did detect equal number of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.5

Other risk factors for VTE that have been identified include increased age, increased ISS, head, thoracic, abdominal, lower extremity, and spinal cord injury. Craniotomy, laparotomy, and spinal operations also associated with VTE.6

EAST and PTS developed a GRADE based guideline with recommendations to not perform routine screening due to the low incidence of asymptomatic patients. They recommended prophylaxis in all patients 15 years and older and younger post-pubertal children with ISS > 25.7

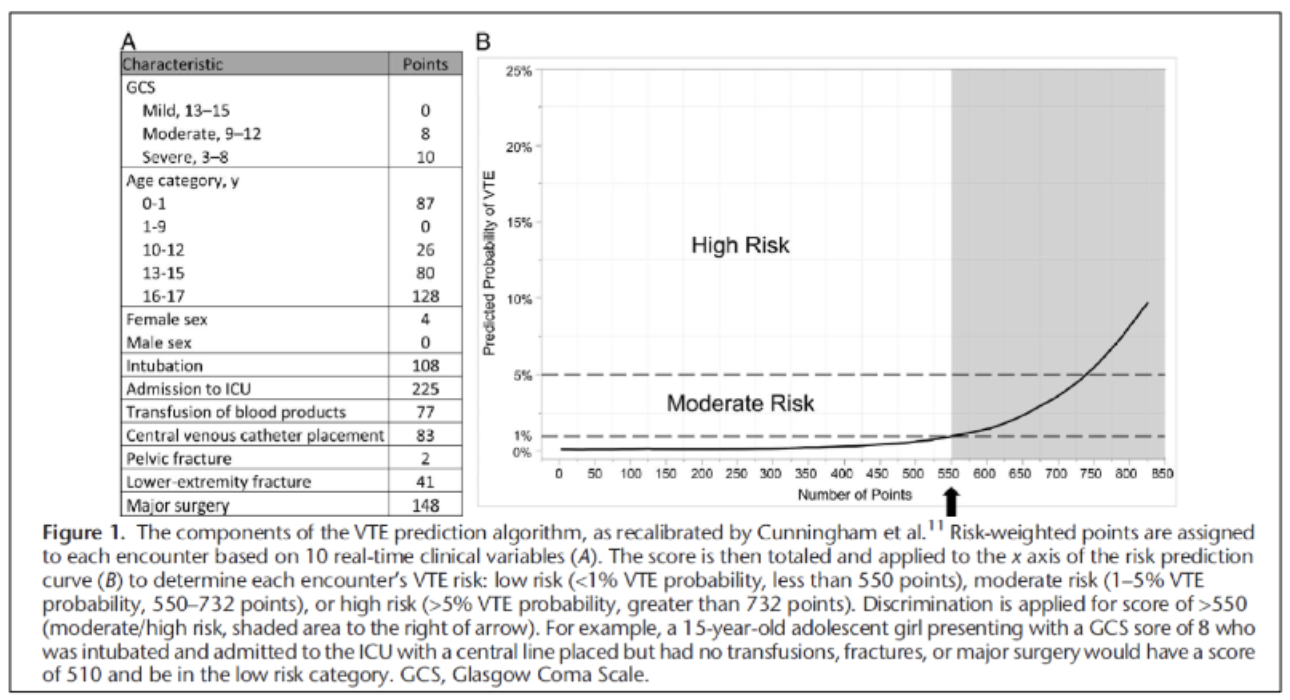

A more complex screening tool developed from the NTDB has recently been developed and validated – this VTE prediction algorithm calculates a risk score. A score greater than 550 indicates moderate risk and potential for needing prophylaxis (Figure 5).8

Figure 5

TREATMENT

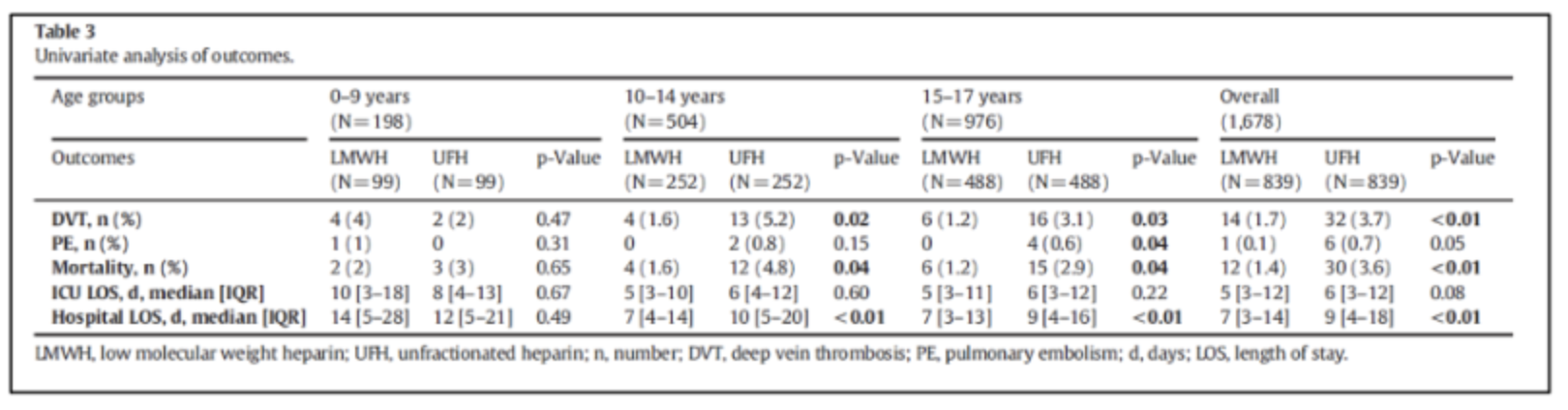

In a Pediatric TQIP study, LMWH was felt to be superior to UFH with respect to prophylaxis. A significant difference in survival DVT events, and in-hospital LOS was seen in the age groups above 9 years. Overall, the patients who received LMWH had lower mortality (1.4% vs 3.6%, p<0.01), DVT (1.7% vs 3.7%, p<0.01), and hospital LOS among survivors (7 days vs 9 days, p<0.01) compared to those who received UFH. There was no significant difference in the ICU LOS among survivors and the incidence of PE between the two groups (Table 2).9

Table 2

References

- Leeper CM, Neal MD, McKenna C, Sperry JL, Gaines BA. Abnormalities in fibrinolysis at the time of admission are associated with deep vein thrombosis, mortality, and disability in a pediatric trauma population. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Jan;82(1):27-34. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001308. PMID: 27779597.

- Derderian SC, Good R, Vuille-Dit-Bille RN, Carpenter T, Bensard DD. Central venous lines in critically ill children: Thrombosis but not infection is site dependent. J Pediatr Surg. 2019 Sep;54(9):1740-1743. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.109. Epub 2018 Dec 27. PMID: 30661643.

- Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Greenup RA, Liu H, Sato TT, Havens PL. Incidence and risk factors for venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma. 2010 Jan;68(1):52-6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a74652. PMID: 20065757.

- Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Arca MJ, Simpson P, Christensen MA, Hanson SK, Yan K, Braun K, Havens PL. Effectiveness of clinical guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 May;72(5):1292-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824964d1. PMID: 22673257.

- Landisch RM, Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Braun K, Cassidy LD, Gourlay DM. Efficacy of surveillance ultrasound for venous thromboembolism diagnosis in critically ill children after trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Nov;53(11):2195-2201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.013. Epub 2018 Jun 20. PMID: 29997028.

- Vavilala MS, Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Mackenzie E, Rivara FP. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in pediatric trauma. J Trauma. 2002 May;52(5):922-7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200205000-00017. PMID: 11988660.

- Mahajerin A, Petty JK, Hanson SJ, Thompson AJ, O'Brien SH, Streck CJ, Petrillo TM, Faustino EV. Prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in pediatric trauma: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma and the Pediatric Trauma Society. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Mar;82(3):627-636. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001359. PMID: 28030503.

- Labuz DF, Cunningham A, Tobias J, Dixon A, Dewey E, Marenco CW, Escobar MA Jr, Hazeltine MD, Cleary MA, Kotagal M, Falcone RA Jr, Fallon SC, Naik-Mathuria B, MacArthur T, Klinkner DB, Shah A, Chernoguz A, Orioles A, Zagel A, Gosain A, Knaus M, Hamilton NA, Jafri MA. Venous thromboembolic risk stratification in pediatric trauma: A Pediatric Trauma Society Research Committee multicenter analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021 Oct 1;91(4):605-611. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003290. PMID: 34039921.

- Khurrum M, Asmar S, Henry M, Ditillo M, Chehab M, Tang A, Bible L, Gries L, Joseph B. The survival benefit of low molecular weight heparin over unfractionated heparin in pediatric trauma patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2021 Mar;56(3):494-499. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.07.021. Epub 2020 Jul 30. PMID: 32883505.

Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open (TSACO)

Big Shoes to Fill

Written By: Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD, FACS

Editor in Chief, Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open (TSACO)

This is my first column for the cutting edge as the incoming editor in chief of Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open (TSACO). I am excited to report to the AAST membership on the success the journal has had under its first editor in chief, Dr. Timothy Fabian. I will also give some information about the future direction of the journal and what the organization’s membership can do to help with TSACO’s mission “To provide the global trauma & acute care surgery community with free access to top-notch scientific information.”

Recently, the AAST and TSACO hosted a Festschrift for Dr. Fabian in Memphis Tennessee. (see photos) Over 100 invited speakers and guests spent the day celebrating Dr. Fabian, summarizing his contributions to the science of trauma, and reminiscing with heartfelt stories and colorful anecdotes about his 40-year career. It was an honor to speak on behalf of the journal. I told the audience that “I have big shoes to fill” in taking over from Dr. Fabian. I won’t recount everything I said here, for that you will need to read the manuscript I wrote summarizing Dr. Fabian’s accomplishments as the journal editor. Read the Manuscript HERE

There is no doubt in my mind that the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) selection of Dr. Fabian was the perfect choice to “give birth to TSACO.” Over the first seven years of TSACO’s existence, he created everything from nothing; crafting the journal’s mission, vision, and goals. TSACO has received over 1000 submissions and published over 600 manuscripts. True to its mission, the journal has published articles of all types from around the globe with research and educational content being submitted from 47 different countries and 6 continents. TSACO is indexed in PubMed Central, listed in the Emerging Sources Citation Index, and we are expecting our first impact factor later this spring.

The Festschrift kicked off with introductory remarks by AAST Past-Presidents David Livingston and Martin Croce. Then, we heard a series of presentations by seven past-Memphis fellows covering some of the landmark papers Dr. Fabian and his team wrote which have changed the landscape of trauma care on important topics including: injury to the liver, spleen, and colon, blunt aortic and cerebrovascular injury, ventilator associated pneumonia, and abdominal wall reconstruction. Each speaker published an accompanying manuscript (in TSACO of course), that are freely available in our open access journal. View the Table of Contents HERE

In following Dr. Fabian my goal is to build upon the incredible bedrock that he founded the journal upon. Our mission is “To provide the global trauma & acute care surgery community with free access to top-notch scientific information.” We strive to accomplish this mission on the backbone of three core strategies: 1) Grow High Quality Research, 2) Enhance Global Communication, and 3) Promote Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion.

My asks of the membership are relatively simple. First and foremost is to submit manuscripts to the journal. We are actively seeking original research, review articles, commentaries, and case reports (called “challenges in trauma and acute care surgery.” We have also created a new article type called “Talks I Have Given.” The first in the series, “Ensuring excellence in patient care, research, and education: thoughts on leadership and teamwork,” was written by AAST Past-President David Spain. This article type includes the slides and the text from a lecture. If you’ve seen an amazing talk that you think the world needs to learn from, email me your suggestion. Second, please review for TSACO if asked. The quality of our publications relies on the peer review process. If you’ve been asked to review, it’s because our editorial team thinks you are an expert in the field and would improve the quality of the manuscript and will help us decide whether it should be published. I don’t take this job lightly and neither should you.

The new TSACO Editorial Team is up and running. We have five new Deputy Editors:

- Matthew Martin, Clinical Content

- Stephanie Savage, Operations

- Jeffry Nahmias, Communication

- Tina Gaarder, Global Strategy / Outreach

- Ajai Malhotra, Global Strategy / Outreach