The most up-to-date information for all things AAST

Expand to Explore

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Taxonomy for Medical Services and Procedures

Healthcare Economics Committee

Artificial Intelligence (AI) Taxonomy for Medical Services and Procedures

Contributing Author: Phillip Kim, MD, MBA

Managing Editors: Raeanna C. Adams, MD, MBA; Samir M. Fakhry, MD, FACS

In September 2021, the American Medical Association (AMA) CPT® Editorial Panel implemented Appendix S, an AI Taxonomy for Medical Services and Procedures, effective January 1, 2022. Developed as a standardized framework for describing how algorithms participate in clinical care, the taxonomy was created ahead of AI-specific CPT codes to prepare for future integration into operative coding and reimbursement. It is intended to clarify terminology, to define expected clinician involvement, and to provide consistency in documentation, though it is not yet directly applied to operative coding. The AI Taxonomy classifies AI-enabled services into the following categories:

- Assistive - detects clinically relevant data without analysis or generated conclusions, requiring the clinician to interpret and report

- Augmentative - analyzes and/or quantifies data to produce clinically meaningful output, which the clinician must interpret and repor

- Autonomous - independently interprets data and generates clinically meaningful conclusions without concurrent clinician involvement

- Level 1—AI draws conclusions and offers diagnosis or management options, requires clinician action to implement

- Level 2—AI draws conclusions and initiates diagnoses or management, option for clinician to override

- Level 3—AI draws conclusions and initiates management, proceeds unless contested by the clinician.

For acute care surgeons, the implications of the AI taxonomy relate to documentation clarity and compliance, code selection, and operational planning. When an AI-enabled tool is utilized (e.g., hemorrhage detection on Computed Tomography for trauma), Appendix S language can help document whether the algorithm was assistive/augmentative or autonomous. Understanding the distinctions between assistive, augmentative, and autonomous AI and the specific level of autonomy exercised allows surgeons to set clear workflows, to determine when human review is mandatory, and to ensure that patient care decisions remain transparent and responsible.

Pre/Postoperative Care: -54 and -55 modifier changes

Healthcare Economics Committee

Pre/Postoperative Care: -54 and -55 modifier changes

Contributing Author: Phillip Kim, MD, MBA

Managing Editors: Raeanna C. Adams, MD, MBA; Samir M. Fakhry, MD, FACS

Medicare payment for most surgical procedures includes the procedure itself as well as all post-operative visits that occur within a defined time (referred to as the Global Surgical Package or Global Period). For a global period of 10 days, there is generally no preoperative period, with a visit on the day of the procedure not typically billable as a separate service. The payment would usually include the procedure day and the following 10 days. For a 90-day global period, it usually includes a total of 92 days, incorporating 1 preoperative day, the operative date, and 90 postoperative days. The breakdown of components (preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative care) of each CPT code can be found in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Relative Value File.

For surgeons who will be transferring postoperative care to another clinician not in the same group (so not considered Same Physician for purposes of billing):

- Modifier -54 (“surgical care only”) is appended by the operating surgeon, and

- Modifier -55 (“post-operative management only”) is appended by the clinician assuming follow-up care. These modifiers “unbundle” the global surgical package, so payment reflects each clinician’s portion of the work, while ensuring the combined payment does not exceed the single global amount. For many 90-day global periods, the post-operative component accounts for approximately 20–25% of total reimbursement, though exact percentages vary by CPT code.

For acute care surgeons — particularly those working at tertiary referral centers — this has important financial and operational consequences. When Dr. Tertiary Care formally transfers post-operative care to another surgeon group within the organization or to a clinician closer to the patient’s home, a claim billed with modifier -54 will typically be paid to the operating surgeon only for the intra-operative portion, often around 70% of the global payment, and prorated postoperative care, as applicable. The process applies in reverse for an acute care surgeon receiving another surgeon’s patient with formal transfer agreement to provide further postoperative care. Relevant critical care unrelated to the procedure itself but still within the global period would be able to be billed with the FT modifier as usual, but floor postoperative notes and office visits related to the procedure would be part of the CPT with modifier -54 payment.

- The transfer must be formalized in writing and agreed upon by the patient or surrogate.

- The transferring surgeon must append Modifier -54.

- The receiving clinician must correctly submit the same CPT code and -55 modifier with the surgery date.

- The date of service is the surgical procedure; thus, the duration and amount of the payment of the global period overall remains unchanged, despite redirection of the payments.

Failure to coordinate proper -54/-55 usage can result in lost reimbursement, compliance issues, and confusion over responsibility for patient care. Understanding and correctly applying these modifiers helps ensure fair payment for the work performed, clear delineation of duties, and smooth care transitions for patients across the acute care continuum.

References:

https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-appendix-s-ai-taxonomy-medical-services-procedures (accessed August 10, 2025)

PFS Relative Value Files | CMS https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/pfs-relative-value-files (accessed August 16, 2025)

MLN907166 – Global https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mln907166-global-surgery-booklet.pdf Surgery (accessed August 19, 2025)

Caring for Injured Children – Why All Acute Care Surgeons Should Contribute!

Pediatric Committee

Caring for injured children – Why all acute care surgeons should contribute!

Contributing authors: Lillian F. Liao, MD MPH, Mary E. Fallat, MD, Elizabeth P. Scherer, MD MPH, Susannah Nicholson, MD, MS

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose, by any other would smell as sweet is merely a label, and does not define the essence of a thing” – William Shakespeare (1590s)

We found the popular Shakespeare line oddly appropriate for this article which aims to provoke discussion among the larger community of acute care surgeons, trauma surgeons, “adult” surgeons, and pediatric surgeons. The labels we choose to identify ourselves are less important than our shared expertise in providing emergency care for all ages – adult, the elderly, and children. In particular, the focus of this article is on 25% of the injured population – the children.

Every ED should be able to provide an airway and vascular access for a severely injured child. Every general surgeon should be able to perform a damage control laparotomy for a child in advanced hemorrhagic shock, followed by a transfer to a Pediatric Trauma Center. This potentially life-saving intervention might not be successful, but what if this was your child or grandchild, your relative, your neighbor’s child? Would you want a trained general surgeon to try?

Injury is and has been the leading cause of death and disability in children in the United States for decades. Vehicular related trauma, firearm injuries, and burns are among the top reasons for injury-related emergency department visits. Care of injured children has long been the domain of pediatric surgeons but there are many communities with a paucity of pediatric surgeons, and some are in remote areas. How are children cared for and by whom? In these same communities, who cares for other surgical emergencies such as appendicitis and soft tissue infections, two procedures which account for nearly 90% of all emergency operations or procedures in children?

Case scenario – You and your family are spending the weekend in a Wyoming cabin. In a moment of weakness, you allow your 8-year-old to drive an ATV across the “flat” plains of the ranch. Unaware of the uneven patch of land ahead, your daughter flips the ATV, is thrown off at 30mph, and lands 20 feet away on a rock. She is crying due to pain when you reach her. She has an open femur fracture and is complaining of abdominal pain. You call 911. The closest hospital is a state Level III adult trauma center 20 minutes away. During the ride to the hospital, the EMS team calls ahead to tell the receiving hospital that her blood pressure is 70/30, heart rate 137, respiratory rate 25, and oxygen saturation 80% on high flow oxygen by bag-valve-mask. The surgeon on call is “uncomfortable” taking care of an 8-year-old. Her abdomen is getting more distended. The FAST is positive. She receives the 1 unit of PRBC that is available, and she is awaiting air transport but progressively declines and suffers a traumatic arrest, which is refractory to resuscitative efforts.

The patient scenario above is exaggerated for effect; however, being overcome by fear is a failure of emergency preparedness. Any well-trained general surgeon should be skilled enough to perform the basic components of resuscitation and have the ability to perform damage control surgery, particularly in an anatomically normal child.

Melhado C, Hancock C, Wang H, et al. Pediatric Readiness and Trauma Center Access for Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2025;179(4):455–462. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.6058

Developing confidence, competence, composure in pediatric trauma care

“Confidence is the belief that you can achieve the goal or task in front of you, even if the odds are against you.” Ronald Stewart, Maine 2023

The small size and sometimes fragile nature of children, the lack of knowledge regarding when to operate and when to observe, lack of understanding of special emotional needs of children, and the “lack of pediatric fellowship training” are some of the most common reasons Acute Care Surgeons/Trauma Surgeons shy away from caring for injured children. We asked experts in the field of pediatric trauma care to discuss important questions the general audience may have regarding the care of children by ACS/Surgical Critical Care-Trauma/General Surgery Board Certified surgeons.

Pediatric readiness is defined as “ensuring that every EMS agency and emergency department has the pediatric-specific champions, competencies, policies, equipment, and other resources needed to provide high-quality emergency care for children”. The ACS COT is a new partner to pediatric readiness. The standard requires that every trauma center verified by the ACS COT is aware of pediatric readiness and has partnered with the emergency department to do a checklist to see how well they compare with hospitals across the country. A perfect score is 100, but the average score of all hospitals who took the survey in 2021 was 70, and we know from a mounting evidence base that a score of 93 or above is needed to realize the mortality benefit from being “pediatric ready”. There are over 5000 acute care hospitals in the country and about half are considered trauma centers (including Level IV and V centers). Since only about 800 hospitals are verified as trauma centers by the COT, the remainder are not currently held to this standard unless the state trauma system requires it.

While critically injured children with multisystem trauma may need to be transferred to a higher level of pediatric trauma center, many children sustaining burns or trauma can be cared for within their communities. If you live in a region where access to a level I or II PTC is more than 60 minutes away, your trauma center should be providing care and be able to stabilize an injured child. The basic tenants of ATLS and surgical hemorrhage control in children are like those of the adult population minus special equipment needed based on size. The development of confidence and competence in caring for children should be approached in manner similar to how we address the needs of the elderly population. Evidence based guidelines for management of solid organ injury, traumatic brain injury, imaging, child maltreatment screening, substance misuse, and mental health screening all exist and are available through national organizations such as the EMSC Innovation and Improvement Center (EIIC), ACS COT, PTS-AAST, EAST, and APSA.

https://emscimprovement.center/education-and-resources/peak/multisystem-trauma/

The community of pediatric surgeons with an interest in Pediatric Trauma is also readily available to offer guidance and mentorship.

“Trauma systems save lives” may be a rhetorical statement for this audience. However, in the development of trauma systems across the country, there is not always a process to incorporate children in the planning and optimization of pediatric care. When there isn’t a pediatric trauma center available within 60 minutes, adult trauma centers and hospitals providing injured care should step in to fill the gap with intentional planning and readiness to care for the injured children. The actionable strategies to provide optimal care for injured children are concisely written in a policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics: The Systems-Based Care of the Injured Child: Policy Statement by Katherine T. Flynn-O’Brien, MD, MPH, FAAP, FACS; Vijay Srinivasan, MBBS, MD, FCCM, FAAP; Mary E. Fallat, MD, FAAP, FACS is a must read for all members of the AAST and the trauma community at large. This is an open access article and can be found here.

Action and Implementation Strategies

- State and federal institutions should financially support pediatric trauma system development and maintenance, disaster planning, data collection and sharing, research, and education.

- Every state or region should identify specialized trauma centers with the resources to care for injured children and establish systems to triage injured children appropriately based on their needs.

- Health care systems should actively participate in and cultivate injury-prevention programming to reduce the rate of pediatric injuries.

- Prehospital and hospital clinicians should make every effort to stay current in the management of injured children, including the ability to evaluate, stabilize, and transfer acutely injured children. Direct feedback from trauma centers can assist with continued process improvement for prehospital teams and agencies.

- Interfacility transfer guidelines and protocols should be in place to facilitate rapid transport of critically injured children to trauma centers that can provide an appropriate level of care. EMS professionals and transport teams with pediatric expertise should be used in the interfacility transport of critically injured children.

- Evidence-based protocols for the management of the injured child should be developed for essential aspects of care across the continuum of care. These should be continuously revised to reflect current evidence, with the goal to improve outcomes after injury.

- Evidence-based mental health screening tools should be developed for use in the acute setting and in follow-up to aid in the early detection of children at risk for development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Those at risk should be provided resources and/or referral for early intervention by mental health professionals trained in trauma-informed care.

- Established performance improvement and quality improvement programs should be established at all centers caring for injured children. Closed loop communication in the form of direct, constructive feedback should be provided by, and to, pediatric trauma centers to allow for continued education and improved pediatric care.

Acute Care Surgery Committee Update

Acute Care Surgery Committee

Acute Care Surgery Committee Update

Written by: Marc de Moya, MD

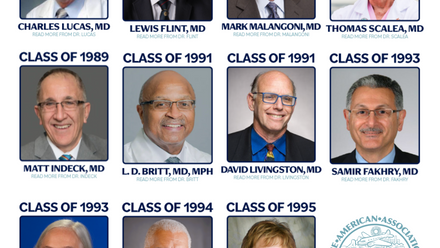

We have had an exciting year and wanted to share some of the highlights with the AAST membership. This year we carried on the work led by Dr. Stephanie Savage and expanded our AAST ACS Fellowship Bootcamp to both the University of Maryland-Shock Trauma Center and LA-County. As hosts, Dr. Inaba and Scalea warmly welcomed the fellows and the guest faculty from across the country. The bootcamp included a cadaver portion that covered tons of pearls/tips/tricks for the advanced trauma surgeon and also a series of lectures/case reviews/skills, including laparoscopic CBD exploration and advanced endoscopy. The bootcamp was supported in part by the AAST and industry sponsorship. We hope to scale things up in 2026 to provide a bootcamp for all 76 AAST ACS Fellows.

We also continued to grow the Educational offerings with modules, journal club, Master Lecture series, and Meet the Mentor programming.

The After-Action Report/Improvement Plan (AAR/IP): Tips for Success

Disaster Committee

The After-Action Report/Improvement Plan (AAR/IP): Tips for Success

Written By: Taylor J. Bostonian, MD; Adam D Fox, DO, FACS; Joanelle A. Bailey, MD, MPH, FACS

In disaster preparedness and emergency response, the After-Action Report and Improvement Plan (AAR/IP) is one of the most powerful tools for transforming experience into meaningful change. Whether the event is a real-world (mass casualty) incident, a simulated disaster drill, or an institutional crisis, the AAR/IP offers a structured opportunity to document, reflect, and, most importantly, improve.

What Is an AAR/IP?

An AAR/IP is more than just a post-event checklist. It is a detailed analysis helping organizations evaluate what happened, why it happened, and how it can be managed differently in the future. It encompasses equal parts accountability and opportunity. It is an iterative tool that, when done properly, can strengthen institutional readiness, formalize best practices, and address mission-critical gaps.

Tips for Success

- Involve the Right People Early

An effective AAR/IP requires multidisciplinary participation. Include voices from all levels: frontline staff, leadership, logistics, and support services. Involvement of stakeholders ensures a comprehensive perspective and builds buy-in for subsequent improvement efforts.

- Be Structured and Strategic

Use established frameworks, such as FEMA’s AAR/IP template or the Joint Commission’s tools, to guide your process. Established templates ensure inclusion of all critical components, from capability analysis to recommended actions for improvement. Standardization in data collection and analysis improve consistency and allow for comparability, which can benefit more than just the institution completing the report.

- Translate Observations into SMART Actions

Issue identification is easy, but providing solutions to address them is much more challenging. Action items should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Assign clear ownership and deadlines to each recommendation so it does not get lost in a binder on a shelf.

- Focus on Both Gaps and Strengths

Too often, AAR/IPs focus solely on what went wrong. However, identifying what worked well is equally as important – sustaining and formalizing strengths as best practices builds both confidence and institutional memory.

- Circle Back

An AAR/IP is only effective if it leads to change. Make it standard practice to revisit the plan, track progress, address roadblocks, and recognize what is and is not working. Building a culture of improvement means holding ourselves accountable long after the event is over.

Bottom Line

An After-Action Report/Improvement Plan (AAR/IP) is a framework for building resilience, not just another mundane task to complete; it should be recognized as an opportunity to improve and not treated as a formality. As trauma surgeons and emergency response leaders, we must make this process part of our day-to-day practice, signaling a deeper commitment to growth, safety, and preparedness. Ultimately, success is not measured by how we perform in the moment, but by how we take what we have learned and make it count.

Research and Education Fund Update

Research and Education Fund

Research and Education Fund Update

Written by: Suresh Agarwal, MD

As excitement builds to the start of the 84th Annual Meeting of the AAST and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery, I am looking forward to meeting old friends, making new friends, and learning about advancements in the care of acutely ill and injured surgical patients from some of the most capable scientific minds in academia. Many of these activities have been directly supported through the kind and generous support that you have provided through the AAST Research and Education Fund (REF).

Your support through initiatives, such as 20 for Twenty, has allowed supplemental funding for travel and registration for medical students, residents, and fellows to attend our annual meeting. As travel funding is being reduced at multiple institutions, these funds ensure that we are able to continue to attract the best and brightest to our field.

The Research Scholarships that are given annually allow for the initiation and continuation of research for junior faculty members. This seed money has frequently been a springboard for leadership development and federal funding for several individuals, providing research support and mentorship necessary to compete in today’s competitive external funding environment. The presentations given by last year’s recipients are always a highlight of the program and demonstrate the potential that our scientific colleagues possess. This year, Melike Harfouche, MD, MPH; Lacy LaGrone, MD, MPH; and Grace Martin Nizolek, MD, will regale us with the progress that they have made since receiving their grants.

As obtaining federal funding becomes more challenging with proposed decreases in overall support to the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation, the scholarships that the AAST REF provides are instrumental in catapulting our junior colleagues towards a successful academic career. Although there are multiple opportunities for philanthropy (as Drs. Foster and Stewart mentioned in a previous newsletter, there are over 1.8 million non-profit organizations), your contributions to the AAST REF assure the success of our profession by making these scholarships and opportunities possible – please consider donating to allow for our collective continued growth and success.

Missed an Issue?

If you missed the last issue or want to revisit past content, you can browse all previous editions on our archive page. Whether you're looking for policy updates, committee highlights, or educational content, it's all there.

The Cutting Edge Podcast

Prefer to listen on the go? The Cutting Edge Podcast brings AAST to life with engaging conversations, exclusive interviews, and behind-the-scenes stories from the world of trauma and acute care surgery.