The most up-to-date information for all things AAST

Expand to Explore

President's Note: March 2026

Executive Leadership

President's Note

Written By: Kimberly A. Davis, MD, MBA

Greetings from the persistently snowy northeast, which is recovering from a deep freeze. I am looking forward to spring, as I am sure many of you are too. I’m excited to highlight upcoming events in Chicago that are relevant to the membership. The first is the 3rd Annual Designs for Implementation conference, held on February 25-26. This conference, supported by CNTR, focused on improving a system to coordinate partners, processes, and tools to ensure that evidence reaches practice equitably and efficiently, better serving the needs of the injured and all patients. Topics included using artificial intelligence to support educational content development and to ensure that content stays relevant and up-to-date. Developing a sustainable system for information dissemination is a key goal of this three-year series.

The second conference is the 2nd Annual Spring in-person Leadership Academy, scheduled for April 7 in Chicago. Drs. Bellal Joseph, Joe Sakran, Jason Smith, Mike Cripps, and Paula Ferrada have developed a comprehensive program addressing the challenges faced by surgical leaders. We are pleased to welcome 28 mid-career surgeons as the fourth class of Academy attendees. This meeting takes place just before the Spring meeting of the Board of Managers and the program committee meeting, led effectively by Raminder Nirula. Thank you to everyone who submitted their abstracts for review. I look forward to seeing how the Annual Meeting comes together.

Finally, please encourage your budding surgeon scientists to submit grant applications for the various scholarships offered through the REF. In addition to our young faculty awards, AAST is developing another grant to support mid-career scientists who may need bridge funding to an R01 or a K grant. Watch the week-in-review for more information when this program launches. I am thankful to Mitch Cohen and all the members of the scholarship committee for their dedication to surgical science.

Executive Director's Report: March 2026

Executive Leadership

Executive Director's Report

Written By: Sharon Gautschy

When March arrives, the AAST Annual Meeting is only six months away. The AAST education staff, Rachel and Kaitlyn, are busy working with the program committee on the schedule, which should be announced in May.

Housing will open on March 16 for the Annual Meeting. Please check your email if you plan to attend. Registration will open in June.

I hope you have been reading the Week-In-Review, which highlights AAST's activities for the upcoming week. Some of these activities include Grand Rounds, WITS webinars, AMC-sponsored professional development webinars, and others. It also lists the due dates for all available scholarships. The Week-In-Review is sent out every Monday. If you haven't received it in your email, please check your junk or spam folder.

Time to Move On

Communications Committee

Time to Move On

Written By: Jennifer L. Hartwell

Nearly 60% of physicians leave their first job out of training within three years.1 This statistic is both frightening and reassuring to new physicians: where you start is not likely where you will end up…but you are not alone.

The top reasons we cite in leaving a job are compensation; weaknesses of leadership or the organization; and feeling undervalued. But leaving a job is a difficult decision and can be quite costly in terms of time and money. So how does one decide it’s time to move on?

Each surgeon has unique ‘anchors’ to their current job. Some are deep: children heavily involved locally in school or activities, nearby aging or dependent parents, a close collaborative activity or grant that would be irreplaceable. Some anchors are ‘shallow’: enjoying the neighborhood you live in but understanding great neighbors can be found anywhere, appreciating a few close colleagues but knowing that great collegial relationships can grow elsewhere and with our national organizations, friendships can remain close indefinitely.

The decision to leave a job is a very personal one. There is no specific time or reason to seek new employment. We each need to understand our own 'leaving threshold', that is, weighing the pros and cons of staying versus leaving. Each surgeon considering a move must deeply consider the reason they desire to leave. What is driving the desire to move and is it fixable? What will be the cost—to relocate, to move a family, to develop a new local network? It’s worth reviewing these essential questions with colleagues, often those outside of your organization, for an objective point of view.

Once the decision is made to move on, there are several predictable steps along the way.

- While job boards, such as those available from our national organizations, can be helpful, the vast majority of surgeons find their next job through personal relationships and referrals. Build your network.

- The lead time contractually required by your current employer prior to leaving varies dramatically with some as short as 30 days and others as long as 180 days. Know your timeline.

- It takes upwards of six months to obtain a state medical license and credentialing at a new organization. Keep all of your professional documents organized and handy throughout your career.

- Moving to a new job is frequently an optimal time to negotiate academic advancement, funding, support staff, or other things that you were unable to secure in your current situation. Know your non-negotiables, your desirables, and what truly doesn’t matter to you.

- While most organizations have boiler plate contracts with little wiggle room for change (including the dreaded non-compete clauses), things like moving costs, specific office space, or new equipment may be items up for negotiation. Your time to ask is before you sign the contract. You don’t get what you don’t ask for.

- While it may feel like a waste of money, you should always have a contract attorney review any contract before you sign. They are the experts in interpreting the contract. Even if you don’t have leverage to change anything within it, you will have a clearer understanding of what you are signing. Ask questions and stay informed.

- Consider logistics such as the timing of selling and buying a home, children’s school schedules, a partner’s need for employment, and the onerous task of moving your household. Be intentional about the timing of your move.

- Most people will say it takes about two years to become familiar with a new organization, hospital, and coworkers. Feeling comfortable in your new environment doesn’t happen quickly. Set your expectations.

Remember: no job is perfect. Eventually, everyone uncovers weaknesses and frustrations in every work environment, no matter how great it seems at the beginning. Whatever stressors or problems you leave in one job will likely reappear in another format in a new job. Prepare for the honeymoon phase to gradually fade and be ready to commit to the hard work of being an active participant in making your new workplace the best it can be for you, your colleagues, and your patients.

Moving is stressful. Period. You should anticipate a range of emotions: excitement, renewal, and peace, as well as anxiety, fatigue, sadness, regret, guilt, and even depression. Part of moving, even across town, is thoughtfully preparing yourself the best that you can to weather the highs and lows of change. Invest in your relationships, take care of your physical and mental health. Ask for help.

In the end, the healthiest place to be is where you feel safe, respected, and appreciated. No amount of money, no title, no fancy corner office can offer these things to you. It will always be about the people. Seek a place where you can thrive…and trust me…it will always be the place where you find ‘your people’.

References:

When Environment Becomes Mechanism: Trauma and the Physiology of Extreme Cold

Prevention Committee

When Environment Becomes Mechanism: Trauma and the Physiology of Extreme Cold

Written By: Brent W. Llera, Rishabh Matta, Gabriel Froula, Lori L. Rhodes, Christina L. Jacovides and D’Andrea K. Joseph

The patient is a 42 year old male involved in a single car crash when his car flipped over after skidding on black ice. He suffered a large laceration to his forehead and face and a brief loss of consciousness. He was able to extricate himself and call for help. At the time of the crash, he was wearing a thin jacket and gloves. He was found in a snowbank by rescue about 2 hours later due to the weather conditions and remoteness of the area. On arrival to the Trauma Bay, his vital signs were significant for bradycardia to 40 bpm, BP of 90/65, GCS of 10 and a core temperature of 27.5 degrees C. Secondary survey was significant for a bleeding laceration to the forehead, abrasions over the abdomen and cold and waxy digits of upper and lower extremities without blanching. He had a positive abdominal FAST.

The recent winter storms and extreme cold as experienced in the majority of the US resulted in 171 deaths across the country1. The cause of death was indirect and direct and ranged from traffic collisions to cardiac events and exposure. The frigid conditions that accompanied the storms are attributed to the disruption of the polar vortices, which are large persistent areas of low pressure and rotating cold air around Earth's North and South Poles2. When disrupted, this rotating mass is released outside of the poles. Warming of the air can lead to instability in the vortices, causing the release of the cold air to move south thus creating an Arctic blast. Or something like that. While the process by which the Arctic blast occurs is not within the area of expertise of an Acute Care Surgeon, management of injuries sustained as a result of extreme cold is certainly within the purview. Additionally, with a mission to prevent injury, researching and educating learners and the community on how this can be avoided is crucial.

Despite the advancement in trauma care, hypothermia remains one of the most predictable and preventable contributors to trauma-related morbidity and mortality. Injured patients who present with hypothermia, defined as a core temperature of < 35 degrees C, suffer poorer outcomes than their peers3. Patients presenting with normal temperature however remain at risk due to loss of body temperature. The term “lethal triad” consists of hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy and has been well-described in the literature4. The combination results in a disruption of the body’s hemostasis with poor clot formation, decreased enzymatic reactions, and worsening acidosis, leading to further disruption and death if uncontrolled. Studies demonstrate a 15% to 47% increase in mortality with patients who present in this state5. Managing a patient’s temperature to avoid deterioration into this phase can be challenging, but even more so in the setting described. As such, the trauma surgeon bears direct responsibility for recognizing hypothermia, preventing its progression, and mitigating its downstream effects regardless of circumstance.

This patient presents a particular scenario where he has suffered both traumatic injury and cold exposure with severe hypothermia. Definitive care and management require intimate knowledge of traumatic injury as well as the risks associated with hypothermia. A simple act such as undressing the patient can be fraught with danger from exacerbating hypothermia to excessive manipulation that can precipitate lethal arrhythmias. There is also the possibility of ongoing hemorrhage compounded by the impeding lethal triad of trauma and he is at risk for cardiac arrest with a body temperature of 27.5 degrees C. While the hypothermia prevention is key and must occur in parallel with resuscitative efforts, a successful outcome in this patient mandates that focused re-warming occurs.

The most common type of injury from extreme cold exposure is frostbite6. The fingers, toes, nose, ears and cheeks are typically affected with freezing of the skin and underlying tissue that can lead to permanent damage and even amputation of extremities7. Secondary infection can occur even if the underlying tissue survives and there can be ongoing fluid losses with the removal of the protective skin covering leading to exacerbating the initial injury. Pre-existing conditions such as Raynaud’s disease, tobacco use, diabetes, extremes of age, and certain drugs can potentiate the effect of the cold8. Sustained cold exposure causes further deterioration to the body and can lead to life threatening arrythmias culminating in cardiac arrest.

Most frostbite cases occur in urban settings, where housing insecurity, substance use, and psychiatric morbidity underlie many presentations. These intersecting vulnerabilities increase exposure risk, delay care-seeking, and complicate longitudinal follow-up. Unsheltered people in urban settings are particularly vulnerable to such injuries. A 2025 Chicago study by Lewer et al. found an incidence rate of over 1,200 frostbite cases per 100,000 life-years among unsheltered patients, with approximately 46 amputations per 100,000 life-years9. Moreover, the psychosocial and structural forces that complicate rigorous evaluation—transience, mistrust of institutions, fragmented healthcare engagement, and competing survival priorities—are also intrinsic to the development and progression of frostbite itself. Many patients present in a delayed fashion after multiple freeze–thaw cycles and are consequently no longer candidates for time-sensitive therapies such as thrombolysis or rapid rewarming, which are well documented to reduce amputation risk when administered within a 24-hour window.

Regarding community efforts to reduce the impact of cold exposure on individuals, many cities have established programs to reduce this risk. In Philadelphia, for example, dangerously low temperatures trigger the activation of a “Code Blue” emergency. The city’s Office of Homeless Services declares and coordinates this city-wide measure, which results in 24-hour patrols to bring people to warm locations, create makeshift warming areas like libraries and recreational centers, increase shelter capacity, and provide people with warm meals and blankets. Other major metro areas such as New York City, Boston, Chicago, and Seattle also have similar protocols in place. Prevention strategies—including timely access to warming centers, distribution of appropriate cold-weather gear, public health cold alerts, and mobile outreach during extreme weather events—remain essential but incompletely studied in this population. A 2025 systematic review by Akhanemhe et al. evaluating interventions to reduce cold-exposure health risks among people experiencing homelessness identified that people experiencing homelessness consistently represent a higher proportion of cold-exposure-related deaths in urban settings and that community-level strategies for injury prevention have been incompletely characterized10. There remains future work to be done to better understand how communities can best protect their populations in extreme weather.

Given the recent extreme cold weather experience by many North American cities, a brief review of best practices for frostbite management is warranted11,12.

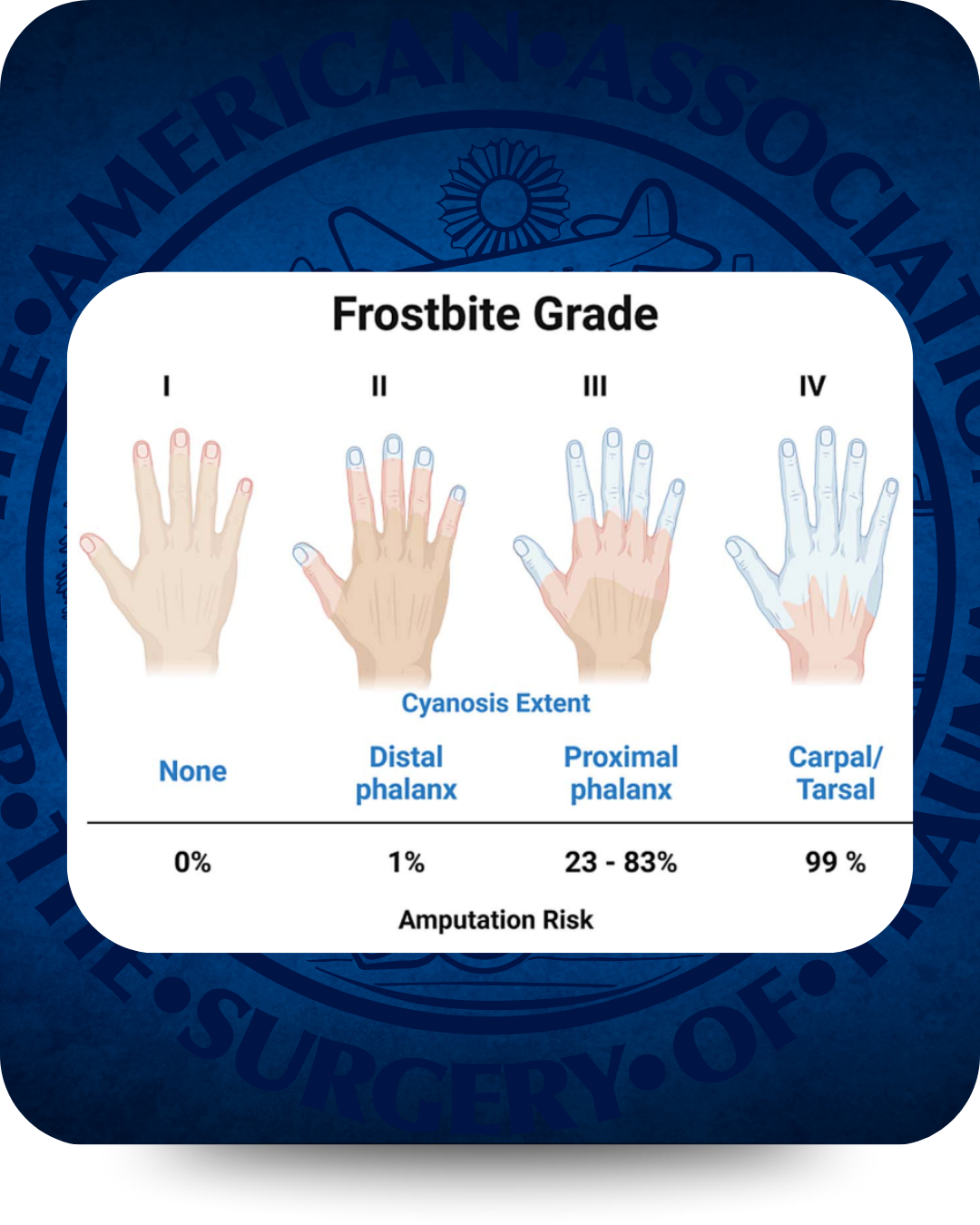

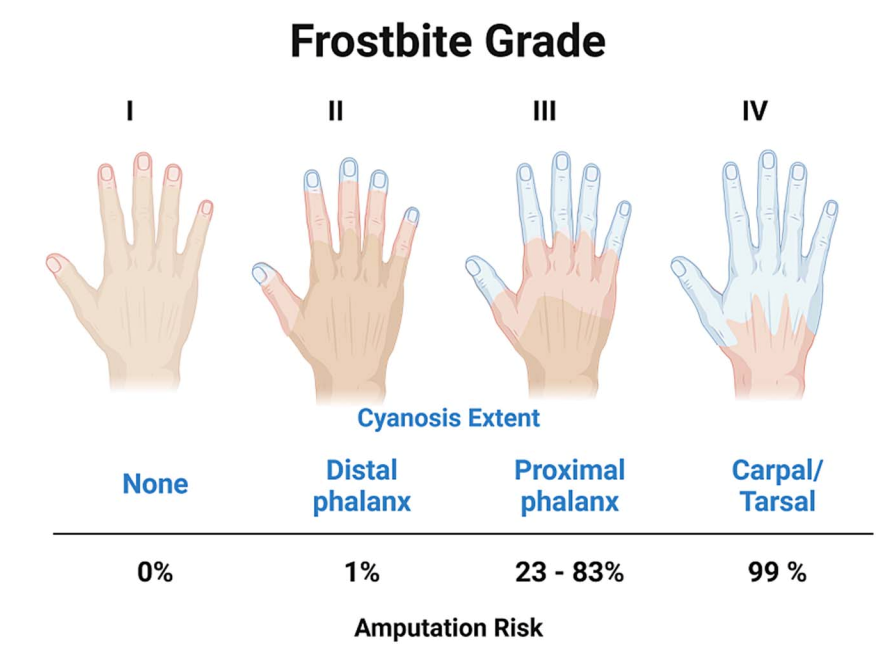

- Frostbite is graded as follows (see image):

- Grade 1 – no cyanosis, amputation rate 0%

- Grade 2 – cyanosis of distal phalanx, amputation rate 1%

- Grade 3 – cyanosis up to proximal phalanx, amputation rate 20-80%

- Grade 4 – cyanosis to metacarpal/metatarsal, amputation rate 100%

- There should be rapid identification and prevention of refreezing since repeated freeze–thaw cycles worsen tissue injury.

- Rapid rewarming in circulating water at 37–39°C should be performed when risk of refreezing has been mitigated.

- Patients should receive appropriate analgesia during rewarming, since the process is often intensely painful.

- Affected tissue should be protected with loose, sterile dressings and by elevating the injured area.

- When no contra-indications exist, there should be early consideration of thrombolytic therapy in severe cases if they present within 24 hours of injury to reduce the risk of amputation.

- Surgical management of affected extremities should be delayed if possible (unless an urgent indication such as infection arises) to allow clear demarcation of nonviable tissue before amputation.

- Use of SPECT/CT can allow for earlier recognition of the necessary extent of amputation. While not necessary in all cases, SPECT/CT can be helpful in a 72-hour window from rewarming for grade 3-4 injuries.

We should note that while it is the most common, there is concern for other types of injury. In addition to the direct injury sustained from cold, patients experience trauma from weather related events. During winter, there is an increased number of falls with concomitant injury. Hip fractures have been shown to increase by as much as a 12.5% over the summer13. Motor vehicle collisions are also noted to increase, rendering the patient scenario above plausible. In fact, one study cited a 19% increase in weather-related crashes during winter months14. Mitigating the effects of the cold involves both passive and active re-warming strategies. Passive measures such as warming blankets and environmental controls should be supplemented with active warming strategies, including forced-air warming device. As a standard, injured patients should be given warmed intravenous fluids and warmed blood products when indicated. Advanced core re-warming techniques include bladder irrigation , warmed humidified oxygen, chest irrigation, peritoneal lavage, and ECMO or cardiopulmonary bypass. The phrase “patient is not dead until warm and dead” is another of the idioms of trauma care. Temperature directed warming techniques should be established with protocols addressing the three levels of patient presentation: Mild Hypothermia —32–35 °C (89.6–95 °F), Moderate Hypothermia — 28–32 °C (82.4–89.6 °F) and Severe Hypothermia — < 28 °C (< 82.4 °F)15. The risk factors associated with each degree of hypothermia should be embedded into these protocols. Importantly, hypothermic cardiac arrest mandates the understanding of the drug function in resuscitation. For example, most drugs will not work if the core temperature is <30 degrees C.

Interrupting the expected increased frequency of Arctic blasts is a discussion for another article. However, it is imperative that it is understood that hypothermia is a preventable phenomenon, and much can be done to prevent it. Establishing management guidelines for patients who present with hypothermia is an essential part of management of patients, but prevention is the first step for any trauma center. Opportunities exist to partner with EMS to create cold weather warming protocols and active rewarming techniques such as the use of heated blankets and adminstration of warm fluid or blood en route. Establishing heated ambulance bays in addition to the trauma resuscitation rooms can help maintain body temperature. Hypothermia should be anticipated in any patient in general, but even more so during winter months and promoting SIM training that establishes best practice for hypothermic exposure is an important part of readiness.

Failure to prepare and plan results in preventable deaths and Trauma surgeons are uniquely positioned to lead this effort. We control the environments, the workflows, and the culture in which hypothermia occurs or is prevented. Temperature management is not ancillary to trauma surgery, but remains fundamental to sound judgment, disciplined decision-making, and effective leadership under physiological stress. Accepting hypothermia as unavoidable is incompatible with modern trauma care.

2. Gibbens, Sarah. "Why cold weather doesn’t mean climate change is fake." National Geographic, 16 Jan. 2024, www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/climate-change-colder-winters-global-warming-polar-vortex

3. González Balverde M, Ramírez Lizardo EJ, Cardona Muñoz EG, Totsuka Sutto SE, García Benavides L. [Prognostic value of the lethal triad among patients with multiple trauma]. Rev Med Chil. 2013 Nov;141(11):14206. [PubMed] [Reference

4. Rotondo, Michael F.; Zonies, David H. (Aug 1997), "The damage control sequence and underlying logic", Surgical Clinics of North America, 44 (7): 761–777, doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70582-X, PMID 9291979

5. Akena P, Kiweewa R, Olum R, Basenero A, Nabulya R, Nabawanuka A, Mugisa D. Factors associated with hypothermia and its response to resuscitation among major trauma patients at St Francis Hospital Nsambya: a prospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2025 Jul 1;25(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12873-025-01254-4. PMID: 40596816; PMCID: PMC12219614.

6. Zaramo TZ, Green JK, Janis JE. Practical Review of the Current Management of Frostbite Injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022 Oct 24;10(10):e4618. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004618. PMID: 36299821; PMCID: PMC9592504.

7. Imray CH, Oakley EH. Cold still kills: cold-related illnesses in military practice freezing and non-freezing cold injury. J R Army Med Corps. 2005 Dec;151(4):218-22.

8. Basit H, Wallen TJ, Dudley C. Frostbite. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536914/

9. Lewer O, Singler C, Wong E, McGinnis D, Nguyen T. Frostbite Injuries in Chicago's Unsheltered Population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2025;36(1):284-294. PMID: 39957650.

10. Akhanemhe R, Petrokofsky C, Ismail SA. Health impacts of cold exposure among people experiencing homelessness: A narrative systematic review on risks and risk-reduction approaches. Public Health. 2025 Mar;240:80-87. Epub 2025 Jan 28. PMID: 39879914.

11. “Frostbite Grading Blue and Red Proximal Extent.” Accessed 15 Feb 2026. https://achpccg.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Frostbite-Grading-Examples.pdf

12. McIntosh SE, Freer L, Grissom CK, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Frostbite: 2024 Update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2024;35(2):183-197.

13. Mirchandani S, Aharonoff GB, Hiebert R, Capla EL, MD, Zuckerman JD, Kova JK. The Effects of Weather and Seasonality on Hip Fracture Incidence in Older Adults. Orthopedics, 2013;28(2):149–155

14. Black AW, Mote TL. Effects of winter precipitation on automobile collisions, injuries, and fatalities in the United States. Journal of Transport Geography, Volume 48, 2015. Pages 165-175, ISSN 0966-6923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.09.007.

15. Perlman R, Callum J, Laflamme C, Tien H, Nascimento B, Beckett A, Alam A. A recommended early goal-directed management guideline for the prevention of hypothermia-related transfusion, morbidity, and mortality in severely injured trauma patients. Crit Care. 2016 Apr 20;20(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1271-z. PMID: 27095272; PMCID: PMC4837515.

From: Schuh JM, Abebrese EL, Morrison Z, Salazar JH. A Frostbite Treatment Guideline for Pediatric Patients. J Burn Care Res. 2025 Nov 5;46(6):1437-1443. PMID: 40849731.

Navigating Equity and Wellness for Underrepresented Surgeons

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee

Navigating Equity and Wellness for Underrepresented Surgeons

Written By: Christine Castater, MD, MBA, FACS

The landscape of surgical training and practice may be evolving, but equity and wellness aren’t optional, they are essential. Underrepresented surgeons including racial/ethnic minorities, women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and others historically excluded from surgery continue to face barriers not faced by the majority as they move through their professional journeys. These barriers range from recruitment and retention challenges in residency, to biased workplace cultures, to inequitable access to mentorship and leadership opportunities. Understanding and addressing these barriers is critical for surgeons and for the patients we care for.

Persistent Gaps and Hidden Costs

Despite decades of inclusive excellence efforts, underrepresentation persists at all stages of the surgical career pipeline. Evidence demonstrates that surgical residencies remain less diverse than other specialties. Institutional and structural factors contribute to lower recruitment and retention of underrepresented surgeons. Moreover, systemic discrimination during training has measurable effects on trainee experience and mental health, with underrepresented residents reporting higher rates of bias and exclusion than their peers.

These inequities compound the emotional burden carried by underrepresented surgeons which contributes to burnout and can influence important career decisions such as fellowship choices. practice setting, and academic engagement. Burnout is already high for surgeons so for underrepresented surgeons, the additional strain of navigating unwelcoming environments or frequently having to “prove oneself” acts as psychological warfare that undermines wellness.

Equity and Wellness

To effectively support underrepresented surgeons, equity must be reframed not as a discrete diversity initiative, but as a foundational pillar of surgeon wellness. Wellness interventions that ignore inequity risk superficiality. For example, generic wellness workshops that do not acknowledge stressors or microaggressions tied to inequities may fail to reach those who need wellness the most.

Equity-focused wellness demands systemic approaches that combine institutional policy, cultural change, structured mentorship, and personalized support. Institutions must gather and report demographic data transparently across recruitment, retention, promotion, and leadership. They should also adopt bias mitigation strategies such as structured interviews and holistic review processes to ensure equitable evaluation of candidates at any level of training or practice.

Wellness is more than just self-care. Organizations must evaluate workload equity, ensure access to mental health resources, and create psychologically safe environments where diversity is valued and resilience is reinforced. Surgical departments should implement mechanisms to identify and address bias or harassment in the workplace swiftly and fairly and these things undermine a progressive work environment.

Wellness programming needs to be culturally responsive. Strategies that resonate with majority groups may not address the lived experiences of underrepresented surgeons whose stressors often include navigating dual identities, combating stereotypes, and being marginalized.

Mentorship, Sponsorship, and Belonging

One of the most powerful drivers of equity and wellness is mentorship. This is especially true when mentorship is deliberate, structured, and supported by the overarching institution. For underrepresented surgeons, access to mentors who understand their struggles and who can help them to navigate the impact of bias, cultural challenges, and professional development is both necessary and invaluable. Institutions that develop programs that pair trainees with diverse mentors early in their careers help them to develop a sense of belonging and long-term engagement.

It is important to remember that mentorship is not enough without sponsorship. Sponsors are leaders who advocate for trainees and junior faculty so that they can successfully achieve promotions, research opportunities, and national visibility. Institutions must incentivize both mentorship and sponsorship of underrepresented surgeons because of the key roles that they both play in academic development.

Interventions That Work

Several structural approaches have demonstrated promise in advancing equity and wellness:

- Longitudinal pipeline programs that engage students from underrepresented backgrounds before medical school have shown benefits in diversifying surgical interest and preparedness

- Institutional committees devoted to inclusivity with dedicated funding and measurable goals help maintain accountability and vision.

- Bias response systems and curricula provide training in equity principles ensure that cultural norms evolve alongside policy changes.

- Transparent pathways to leadership that include sponsorship ladders and equitable nomination processes as well as prevent the “minority tax” of extra service without advancement.

Ultimately, navigating equity and wellness for underrepresented surgeons requires a culture where diversity is expected, wellness is valued, and individual success is tied to institutional support. This culture cannot be imposed from the top; it must be the shared goal of the entire team. The focus must be to support surgeons at every level, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds whose voices are often marginalized.

To do any of these things, we must commit to metrics that matter. The focus can’t be on numeric diversity alone, but on retention, satisfaction, psychological safety, and equitable career development. In doing so, we do more than support underrepresented surgeons. We strengthen the surgical profession as a whole and enhance the care we provide to our diverse society.

Wilson, S.B., Arora, T.K., Abdelsattar, J.M. et al. Supporting diversity, equity, & inclusion in surgery residencies: creating a more equitable training environment. Global Surg Educ 2, 12 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-022-00091-4

Strong BL. Diversity, equity and inclusion in acute care surgery: a multifaceted approach. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2021;6:e000647. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2020-000647

Yuce TK, Turner PL, Glass C, et al. National Evaluation of Racial/Ethnic Discrimination in US Surgical Residency Programs. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(6):526–528. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0260

Byrd JN, Huynh KA, Aqeel Z, Chung KC. General surgery residency and action toward surgical equity: A scoping review of program websites. American Journal of Surgery. 2022;224(1):307-312. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.03.013

Rasic, G., Jung, S., A. Dechert, T. et al. A national survey of diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in general surgery residency programs. Global Surg Educ 3, 102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00298-7

Strong BL, Silverton L, Wical W, Berry C, Brasel KJ, Henry SM. Reaching back to enhance the future: the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Pipeline Program. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2024;9:e001339. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2023-00133

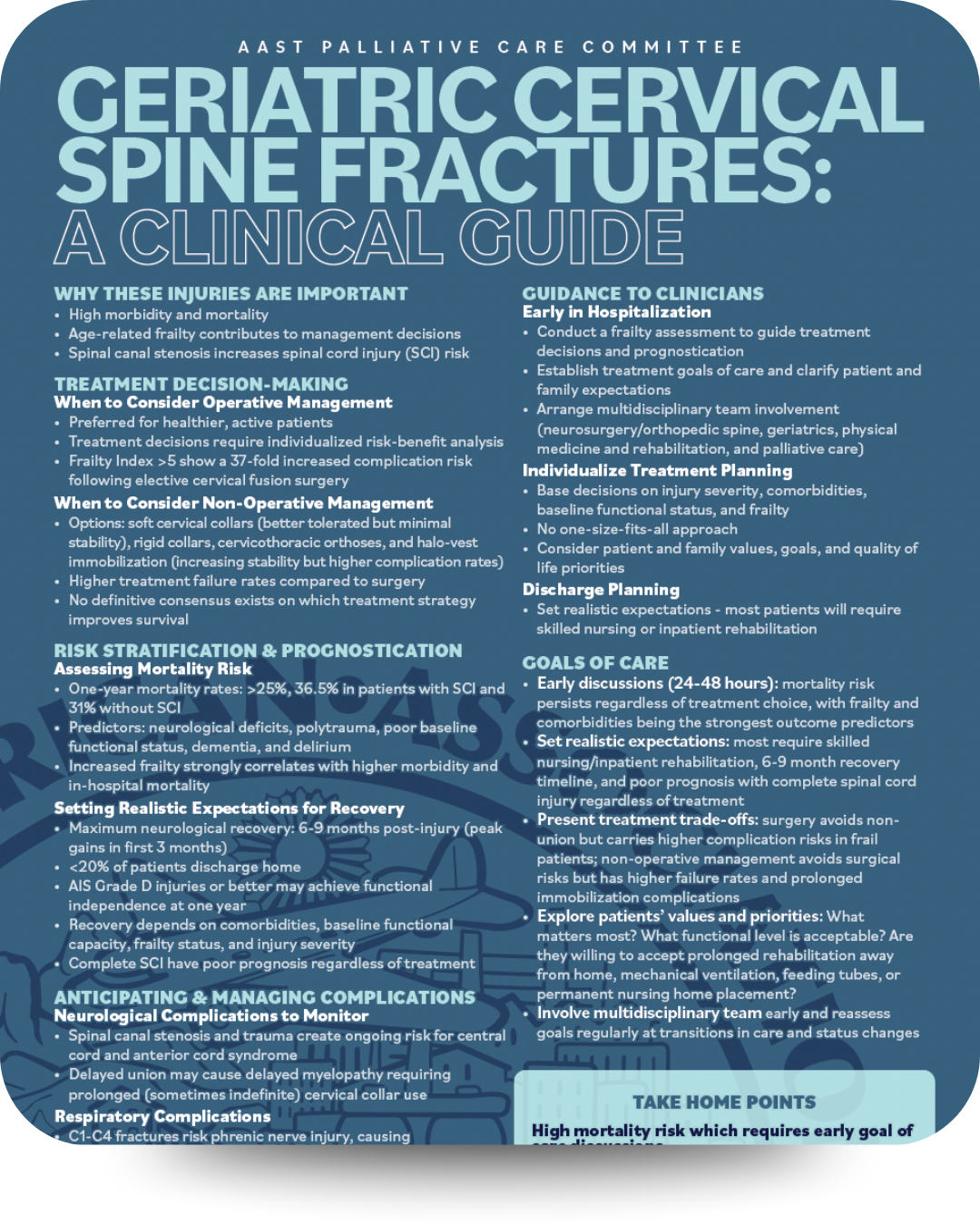

Geriatric Cervical Spine Fracture Management

Palliative Care Committee

Geriatric Cervical Spine Fracture Management

Written By: Tori Wagner, MD

Cervical spine fractures in the elderly patient represent a significant clinical challenge, with mortality rates exceeding 25% at one year. As the population ages, trauma surgeons increasingly encounter these complex cases that require clinical expertise and an understanding of frailty, realistic prognostication, and early goals of care discussions.

Cervical spine fractures in geriatric patients differ fundamentally from those in younger populations. Age-related changes create a perfect storm: osteoporotic bones, degenerative spinal changes, and decreased physiologic reserve, combine to transform low-energy mechanisms into life-threatening injuries. Frailty serves as both a risk factor for sustaining these injuries and a critical determinant of outcomes. The Modified Frailty Index has been identified as an independent predictor of mortality in elderly cervical spine fracture patients, regardless of treatment approach.

Treatment decision-making remains controversial with no definitive consensus on which approach improves survival. Operative management aims for stable fixation and early mobilization, but requires careful risk-benefit analysis, as patients with a Modified Frailty Index (mFI-5) greater than 5 face a 37-fold increased complication risk. Non-operative approaches range from soft cervical collars (better tolerated but providing minimal stability) to halo-vest immobilization (maximum stability but highest complication burden including pin site infections and poor elderly tolerance). Overall, non-operative management demonstrates higher treatment failure rates (see below), yet observational studies present conflicting data about mortality benefits between approaches.

Mortality rates are significant, with one-year mortality reaching 36.5% in patients with concurrent spinal cord injury and 31% without cord involvement, including central incomplete spinal cord injuries. Multiple factors predict poor outcomes including neurological deficits, polytrauma, diminished baseline function, comorbidities (particularly dementia), and delirium, with frailty emerging as perhaps the most powerful predictor. Maximum neurological recovery occurs within 6 to 9 months post-injury with peak gains in the first 3 month;, yet fewer than 20% of patients achieve direct discharge to home. Most patients require skilled nursing facilities or inpatient rehabilitation, with outcomes heavily dependent on pre-existing comorbidities, baseline functional capacity, frailty status, and injury severity. Patients with complete spinal cord injuries face particularly poor prognoses regardless of treatment, while those with incomplete injuries graded as AIS D or better have the greatest potential for functional independence.

Complications extend beyond the initial injury. Spinal canal stenosis and the traumatic insult create ongoing vulnerability for central and anterior cord syndrome, even after fracture healing. Delayed fracture union may precipitate delayed myelopathy, necessitating prolonged cervical collar immobilization and creating cascading problems including skin breakdown, dysphagia, and functional decline. Fractures involving C1 through C4 carry phrenic nerve injury risk, resulting in diaphragmatic weakness, respiratory insufficiency, and impaired cough mechanics that dramatically elevate pneumonia risk. Even without direct nerve injury, patients face immobilization-related atelectasis, aspiration risk, and difficulty clearing secretions. Dysphagia represents a frequently overlooked but critically important complication. Many elderly patients have baseline swallowing difficulties that cervical immobilization devices significantly exacerbate by restricting laryngeal elevation and limiting compensatory head positioning. Early speech-language pathology consultation can identify aspiration risk and guide dietary modifications. For patients with severe dysphagia, goals of care discussions regarding feeding tube placement become necessary, with decisions individualized considering prognosis, patient values, and whether artificial nutrition aligns with overall treatment goals.

The initial 24 to 48 hours are critical for establishing care trajectory. Comprehensive frailty assessment provides prognostic information, while early goals of care discussions are essential given substantial mortality risk. These conversations should involve the patient when possible and family members, presenting realistic outcome expectations. Multidisciplinary involvement improves outcomes, with core team members including neurosurgery or orthopedic spine surgery, geriatric medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and palliative care. Early palliative care involvement ensures symptom management and communication align with patient values without abandoning curative approaches.

No universal "best" treatment exists. Decision-making must integrate injury severity and stability, neurological deficit presence and degree, patient age and physiologic reserve, comorbidity burden, baseline functional status, frailty assessment, patient and family values, and available post-acute care resources. Surgery may be appropriate for relatively healthy 70-year-olds with unstable fractures, good baseline function, and family support, while non-operative management might better serve frail 90-year-olds with advanced dementia, multiple comorbidities, and minimally displaced fractures. The key is matching treatment intensity to the patient's overall condition and goals rather than applying age-based cutoffs or defaulting to a single approach.

Goals of care conversations require skill, empathy, and honesty. High mortality demands early goals of care discussions as an essential component of quality care, with frailty assessment providing critical prognostic information. Clinicians must clearly communicate realistic treatment trajectories and treatment trade-offs. Exploration of patient values is essential: What matters most? What functional level would be acceptable? Are they willing to accept prolonged rehabilitation away from home? Would they want mechanical ventilation or feeding tube placement? Aligning medical interventions with patient values requires explicit discussion, and for patients with very poor prognoses, introducing comfort-focused care as an alternative to aggressive intervention may be appropriate. The absence of consensus on optimal management reflects the heterogeneity of both injuries and patients, requiring individualized treatment that balances injury severity, comorbidities, baseline function, frailty, and patient values. The reality of limited return to baseline function necessitates early multidisciplinary involvement with realistic expectation-setting to prepare patients and families for the likely trajectory.

As the population ages, trauma surgeons will encounter these injuries with increasing frequency. Success requires not only technical skill in fracture management but also knowledge in geriatric medicine, prognostication, and goals of care communication. Recognizing that high-quality care sometimes means intensive treatment and other times means prioritizing comfort and dignity allows us to serve elderly patients in accordance with their values and goals, not just our capabilities. (I like this sentence – well done)

The AAST Palliative Trauma Committee has created a “Geriatric Cervical Fractures” One-Page summary of this information. Please download it from the website, hang in the ICU, the resident workroom and other spaces where it can be referenced.

Frailty First: Risk Stratification and Protocolized Care for the Geriatric Trauma Patient

Geriatric Committee

Frailty First: Risk Stratification and Protocolized Care for the Geriatric Trauma Patient

Written By: Melissa A. Hornor, MD, MS

The demographic landscape of trauma care is shifting, with patients aged 65 and older representing a rapidly expanding proportion of admissions. For this population, clinical outcomes are often dictated more by physiological reserve and pre-existing vulnerabilities than by the kinetic energy of the injury mechanism itself. To optimize care, the trauma community must transition toward nuanced, protocolized care guided by geriatric-specific risk and frailty assessments.

The Prognostic Power of Frailty

Frailty—a multisystemic syndrome of decreased physiological reserve—is a superior predictor of adverse outcomes compared to age alone. Frail trauma patients face a three-fold increase in in-hospital mortality and failure-to-rescue, alongside a three-fold increase in hospital length of stay. Complications are frequent; frail patients are four times more likely to develop delirium and five times more likely to require discharge to a skilled nursing facility rather than home.

This vulnerability is rooted in "inflammaging"—a heightened, prolonged inflammatory response characterized by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1B, IL-6, TNF-Alpha) that leads to secondary organ damage. Furthermore, the aged vascular system responds differently to shock; geriatric patients show a paradoxical decrease in endothelial glycocalyx shedding, resulting in a thinner, more dysfunctional endothelium. These changes extend to every organ system, from sarcopenia and reduced cardiac reserve to altered coagulation cascades, making the fields of "Resuscit-aging" and "Coagul-aging" critical for modern trauma surgeons and future research pathways.

Risk Stratification at the Bedside

Traditional scoring systems like the injury severity score (ISS) or trauma and injury severity score (TRISS) often fail to accurately predict the outcomes of the injured older adult, necessitating specialized tools:a

- Geriatric Trauma Outcome Score (GTOS): Uses age, ISS, and 24-hour transfusion requirements to rapidly estimate mortality.

- Elderly Mortality After Trauma (EMAT): Offers "quick" and "full" versions via a mobile app, incorporating acute physiology (i.e., GCS, SBP, pulse) and comorbidities (i.e., congestive heart failure [CHF], cirrhosis).

- Futility of Resuscitation Measure (FoRM): Developed in 2024, this tool uses age, frailty, and injury characteristics to identify patients for whom aggressive resuscitation may be medically futile (e.g., a score >20 correlates to a 95% mortality rate).

Frailty as an Iceberg and Screening

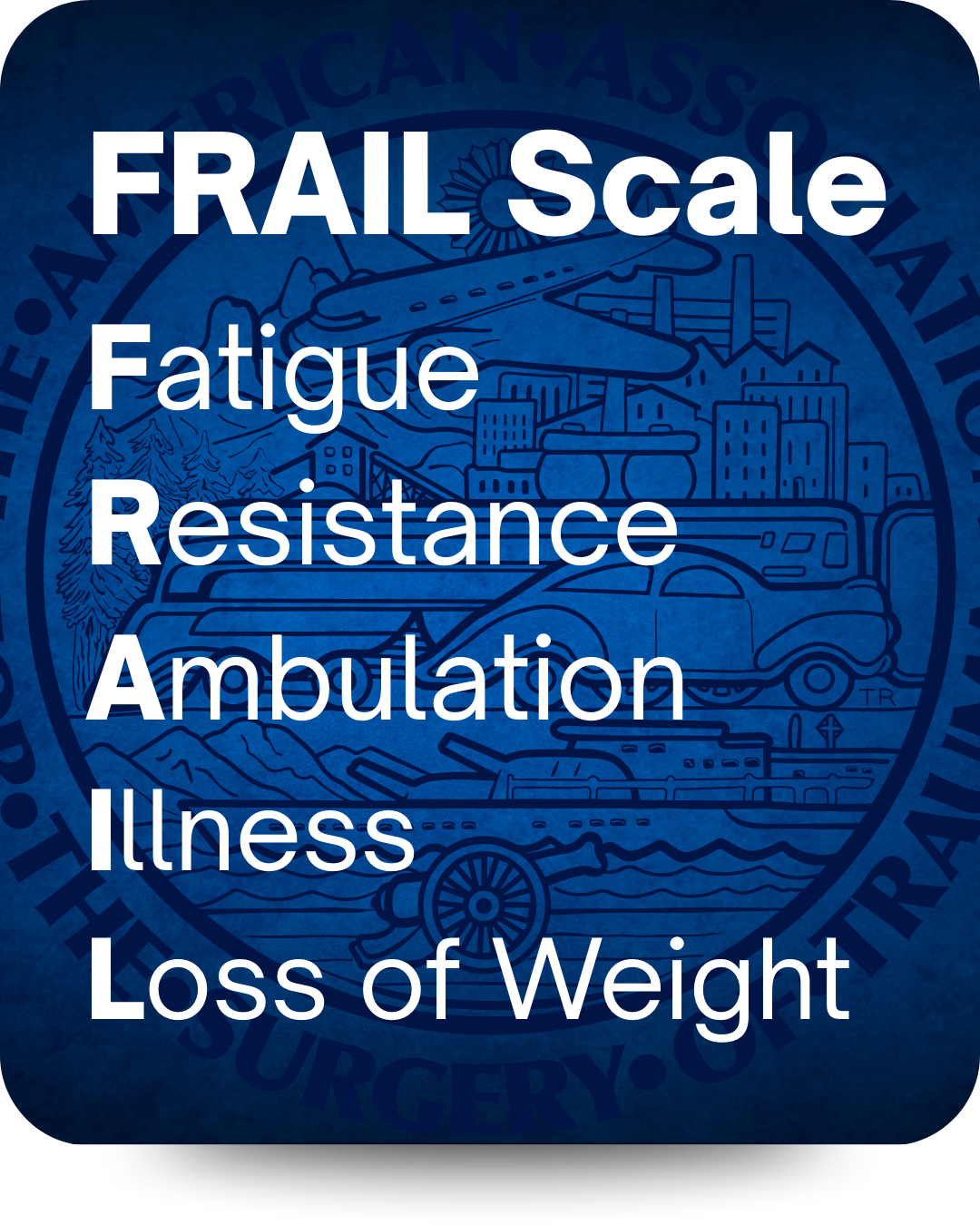

In geriatric trauma patients, the presenting injury is often just the "tip of the iceberg," with "hidden problems" like cognitive decline, polypharmacy, and malnutrition submerged below the surface. Neglecting these factors leads to functional decline and poor surgical outcomes. The ACS Committee on Trauma now mandates vulnerability screening for geriatric populations at Level I and II centers. While several models exist, the Trauma-Specific Frailty Index (TSFI) is the gold standard, using 15 variables to categorize patients as nonfrail, prefrail, or frail. Alternatively, the five-point FRAIL scale (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, Loss of weight) is another option that provides an efficient screening trigger for specialized geriatric interventions.

Translating Evidence into Protocolized Care

Geriatric-specific order sets ensure that evidence-based best practices are applied consistently. These sets should focus on several critical domains:

- Resuscitation: Recognition of occult hypoperfusion (base deficit £ 2 mmol/L despite "normal" vitals) is vital. Order sets should include IVC ultrasound protocols to guide individualized fluid needs. * Medication Management: Automatic flagging of Beers Criteria medications is essential. Strategies should prioritize multimodal, opioid-sparing pain control, such as scheduled acetaminophen and regional analgesia, while avoiding inappropriate agents like ketorolac in those over 65.

- Delirium Prevention: Standardized bundles (e.g., the Hospital Elder Life Program [HELP]) can reduce delirium incidence by 53%. Interventions include sleep hygiene, early mobilization (within 24 hours), and minimizing overnight interruptions.

- Multidisciplinary Engagement: Automatic triggers for geriatric consultation, physical/occupational therapy, and dietary services should be built into the workflow, organized around the 4M framework: Medication, Mentation, Mobility, and What Matters.

System-Level Improvements and Triage

To improve outcomes, trauma systems must address the high rates of geriatric undertriage, which can reach 57% in patients over 80. This is largely due to unreliable vital signs. Mortality risk for older adults begins to rise sharply at age 55 (suggesting "55 is the new 65" for trauma risk) and at SBP thresholds below 110 mmHg.

The ACS now recommends using SBP < 110 mmHg as a geriatric-specific activation criterion to capture occult shock. Furthermore, high geriatric case volume is independently associated with decreased mortality, suggesting that frail patients benefit significantly from care at high-volume, Level I/II trauma centers.

Conclusion

The future of geriatric trauma care lies in recognizing that age is just a number, but frailty is a diagnosis. By integrating validated stratification tools, protocolized order sets, and system-level triage modifications, trauma centers can move beyond treating just the injury to treating the whole patient—improving both survival and the ultimate goal: a return to functional independence.

Resources:

Social Media: A Double-Edged Sword in Disaster Response

Disaster Committee

Social Media: A Double-Edged Sword in Disaster Response

Written By: Meredith Hanrahan, MD and Lori Rhodes, MD

In the midst of natural disasters and humanitarian crises, timely information and coordinated efforts are critical. In recent years, social media platforms have emerged as powerful, but complex tools in disaster response, offering both significant opportunities and challenges.

The primary advantage of social media in disaster scenarios is the ability to facilitate real-time information dissemination. This allows emergency management agencies to broadcast critical updates, evacuation orders, and safety instructions to a wide audience almost instantaneously. Additionally, individuals in affected areas can use social media platforms to report their status, share urgent needs, and provide vital on-the-ground intelligence. This "citizen reporting" can help first responders prioritize efforts and pinpoint areas requiring immediate assistance.

Social media fosters community resilience and organization. Platforms often become virtual hubs for volunteers to coordinate relief efforts, launch fundraisers, and offer support to those in need. For example, hashtags dedicated to specific disasters can quickly aggregate information and connect individuals with resources.

Despite its potential, social media in disaster response can have drawbacks. The rapid and uncontrolled spread of information can lead to misinformation and disinformation, causing panic, confusion, and diverting valuable resources. Rumors about impending threats, false reports of aid distribution, or misleading instructions can severely hinder response efforts and even endanger lives.

The sheer volume of data generated during a crisis can also overwhelm emergency responders, making it difficult to sift through the noise and identify actionable intelligence. The digital divide can also exacerbate inequalities, as those without access to technology or reliable internet may be left out of crucial information loops.

Moving Forward: Best Practices and Future Directions

To maximize the benefits and mitigate the risks of social media in disaster response, best practices have emerged. Organizations from universities to local government agencies are increasingly developing dedicated social media strategies, training personnel in its effective use and establishing clear protocols for information verification.

An effective social media strategy for crisis response is built on three key stages:

- Preparation (Before the Crisis): The priority is to build a trusted and credible online presence. This is achieved by regularly sharing valuable content like preparedness tips and agency news to grow an engaged following. Internally, organizations must establish a clear crisis communication plan with defined roles and pre-drafted message templates to enable a quick and accurate response when needed.

- Response (During the Crisis): Communication must be clear, consistent, and actionable. While speed is important, accuracy is non-negotiable. Resources must be allocated to actively monitor for and correct misinformation to protect the integrity of public information.

- Recovery (After the Crisis): The focus shifts to disseminating information on recovery efforts, aid, and community resources. Within the organization, a thorough post-event analysis of social media performance is critical to identify lessons learned and improve strategies for the future.

Ultimately, social media, when used responsibly and strategically, can be an invaluable asset in saving lives and rebuilding communities in the aftermath of a disaster. However, recognizing its limitations and actively working to overcome them is essential for truly harnessing its potential.

Sources:

Starbird, K., & Palen, L. (2010). Pass it on?: Retweeting in mass emergencies. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM).

Houston, J. B., Hawthorne, J., Perreault, M. F., Park, E. H., Goldstein Hode, M., Halliwell, M. R., & Griffith, S. A. (2014). Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery. Disaster Health, 2(1), 1-13.

Reuter, C., & Kaufhold, M. A. (2018). The impact of social media on citizens' willingness to cooperate in emergencies. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 257-268.

Triaging Trauma Patients in Natural Disaster Events

Disaster Committee

Triaging Trauma Patients in Natural Disaster Events

Written By: Jacob Menzer, MD and Lori Rhodes, MD

A natural disaster is defined as a natural, destructive event that poses risk to human life and property and over the past decade the United States has seen an increase in these events. It is paramount that hospitals across the country can treat victims of natural disasters as these events are not exclusive to one specific geographic region. The healthcare collapse that happened during Hurrican Katrina in 2005 highlighted that hospitals are not adequately prepared to treat patients during a natural disaster. Since then, healthcare infrastructure has evolved to withstand a natural disaster, as evident by Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Though a less severe storm, the hospitals and patients in Harris County, Texas faired better than those in New Orleans in 2005. Despite advances in infrastructure, what remains challenging in natural disasters is balancing the number of patients with the capabilities of a hospital thus underlining the importance of triaging.

Traumatic injuries during any natural disaster arise from the collapse of structures resulting from the brute force of nature, whether that be strong winds, fires, or floods. Falls, crush injuries, head injuries, and fractures are common blunt injuries that will be seen while common penetrating injuries are lacerations from fast moving debris. One also must account for the possibility of concurrent burn injury in any natural disaster victim. While ATLS’s ABCDE algorithm is the gold standard for assessment and initial treatment of trauma patients, its goal is to quickly identify life threatening injuries and temporize patients until definitive treatment. Notably, this algorithm lacks the ability to easily and quickly triage patients to allow for resource allocation in natural disasters.

In the pre-hospital setting, first responders perform a primary triage which directs critical patients in need of care to the hospital. In the hospital, a secondary triage evaluation should be performed by trauma providers to determine the need for further workup or immediate surgery. The military has extensive experience in triaging patients during mass casualty scenarios and proposes the use of “TTT (Time-Treater-Treatment)”. TTT asks three critical questions to frame where patients need to go upon arriving at the hospital: How much time to deliver care, what healthcare providers are needed, and how many resources are needed to provide treatment. In natural disasters there will be a high volume of patients falling into category of needing immediate surgery, which then prompts providers to further triage based on hemodynamic stability, body cavity of injury, salvageability of injured organ, and if any temporizing measures could be performed to buy time until surgery.

Unfortunately, there is no validified or widely studied in-hospital triage algorithm that trauma surgeons can use during a natural disaster. However, the ASPR provides a comprehensive review paper that highlights important trauma triage topics. The National Trauma and Emergency Preparedness System is being actively developed as a way for physicians nationwide to practice standard of care trauma treatment in disaster settings. Additionally, AAST website provides great sources for providers trying to navigate and run a healthcare system during disasters.

Resources:

ASPR: Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response

NTEPS: National Trauma and Emergency Preparedness System

AAST: The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, Disaster Management

March 2026: Research and Education Fund Update

Research and Education Fund

Research and Education Fund Update

Written By: Suresh Agarwal, MD, FACS, FCCM

The Research and Education Fund is the philanthropic arm of the AAST which raises money for the scholarships that make the resident and medical student grants and junior faculty fellowships possible. These activities are essential to help expose future trauma surgeons to our Association as well as provides funding and mentorship for aspiring trauma surgeon- scientists to become successful in driving innovation in the management of the injured patient.

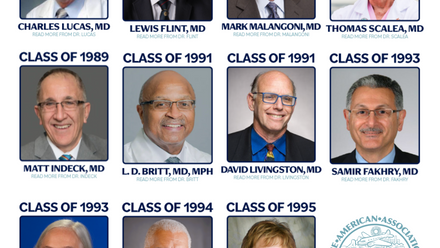

Through the generosity of the membership we had a banner year in 2025! For the first time ever, we raised over $200,000 from 203 individual donors. In addition, the items donated by 25 people for the Experience AAST Auction raised at the Annual Meeting another $85,000, with the Boston Red Sox Raffle adding another $400. Those combined led to a total close to $200,000 for the year – by far the most that was raised in a single year.

We hope that 2026 will be even more successful as we have set our goals for raising over $250,000 in donations and encouraging at least 250 individual donors. Through your charitable contributions, we certainly see the future of trauma and acute care surgery becoming brighter still.

The Whole Surgeon

Get to Know Your AAST Colleagues

Click Here to Read 'The Whole Surgeon'

Rachel M. Russo, MD, MAS, NHDP-BC, FACS

What is a hobby or creative outlet that brings you joy?

One of my favorite creative outlets outside of work is woodworking. I love building furniture tailored to my family’s needs, and it’s a hobby rooted deeply in my childhood. I spent countless hours in my grandfather’s workshop—he was a meticulous craftsman—and my grandmother was right there alongside him. To this day, the smell of sawdust still feels like home.

I’ve kept learning over the years, thanks to generous surgeon-woodworkers who share tips… and more YouTube tutorials than I’d like to admit. What keeps me hooked is that every project teaches me something new. One build might be about figuring out glass-front cabinet doors, another about experimenting with different joinery for dining tables, another about sneaking electrical conduits inside a fireplace surround, or mastering a paint sprayer and new routing techniques for my office bookcases.

It’s hands-on, tactile, and incredibly grounding—and yes (because someone always asks), my fingers are insured.

What is an adventurous or sporting activity that you love—even though you are a trauma surgeon?

Skiing has become my family’s favorite shared adventure… and for me, a personal exercise in managing anxiety. I didn’t grow up around snow (Florida kid!), and my first time on the slopes wasn’t until medical school, when I visited friends in Vail. I switched from snowboarding to skiing once my kids were old enough for lessons, mostly so I could keep up with them.

But here’s the twist: as a trauma surgeon, I know exactly how many ways skiing can go wrong. So yes—I am a nervous skier! It took years to push past the fear and finally reach a point where I can relax and actually have fun. My family loves the sport, and now I genuinely enjoy the time we spend together on the mountain… even if my kids already ski circles around me.

We mostly ski Tahoe, but we’ve been lucky to ski in beautiful places around the world thanks to work-related travel. One day we hope to ski all seven continents—at which point I’ll proudly claim the title of “most cautious adventurer.”

Susan Kartiko, MD, PhD, FACS

How do you spend your time away from work?

The things I like to do when I am away from work is spending time with my family. We have recently taken up golf as a family so when the weather is nice, we spent as much time as possible playing golf.

What is a hobby or creative outlet that brings you joy?

My hobby is to bake and cook. My favorite things to bake are cakes. I believe that the best cakes are flavored with fruits. So I have been developing recipes with different types of fruits. Sometimes it works well and sometimes, terribly! I also enjoy cooking and have been trying to rewrite our old family recipe. Some of the ingredients are so old school that I have to substitute them around, it is a bit like a chemistry lesson.

What is an adventurous/sporting activity that you love EVEN THOUGH you are a trauma surgeon?

The last “adventurous” thing I did was the training for our STRIKE team. This is when we as trauma surgeon would go with the paramedic to render care for patients who cannot be transported to the trauma center and would need some sort of surgical intervention in the field. We had to crawl in tunnels, go under the metro subway track. Otherwise, I am not really keen on anything “adventurous” I rarely ever jaywalk

What is a place worth every penny that recharges you?

The place that is worth every penny that recharges me is vacationing in Hawaii. Our family has an affinity to the beach and there is something is the air in Hawaii that makes us feel very relaxed. Too bad can’t do it too often!

Best memory from an AAST interaction:

The best memory that I have from an AAST interaction is being a part of the DEI committee outreach program to educate high schoolers on how to do research. I have done this for the past couple of years now and every time we do it, I am always amazed at how bright these kids are!

Pranamya Mahankali, DO

How do you spend your time away from work?

Outside of work, I spend as much time as possible with my two girls and my husband, focusing on being fully present and embracing the spontaneous moments that remind me why I work hard in the first place. Whether we’re at home, outdoors, or simply enjoying everyday life together, those moments help me reset and reconnect after the intensity of the hospital.

What is a hobby or creative outlet that brings you joy?

Medical and surgical training can make hobbies difficult to sustain, but as I approach the end of fellowship, I’m intentionally re-engaging in creative outlets that bring me joy, currently it's Yoga, Painting and Pottery.

What is an adventurous/sporting activity that you love EVEN THOUGH you are a trauma surgeon?

Living in the desert, it’s impossible not to love hiking. Getting out on the trails is both grounding and energizing. And in a different sense, traveling across the country and even internationally with young children has become its own kind of sport.

Best memory from an AAST interaction:

Attending my first AAST conference as a fellow in Boston in 2025, my most memorable experience was finding a sense of community. Connecting with surgeons nationwide who are deeply passionate about trauma surgery and driven to advance the field reinforced my desire to be actively involved in AAST.

Featured Investigator Resource:

NTRR Webinar Series (On Demand)

AAST is pleased to highlight an on-demand three-part webinar series from the Coalition for National Trauma Research (CNTR) focused on the National Trauma Research Repository (NTRR). Presented by NTRR Operations Manager Nick Medrano, the series walks investigators through NTRR account types, available modules, and step-by-step data submission. Together, these sessions provide a practical introduction for researchers interested in accessing, managing, or contributing trauma study data to the repository.

NEW Cutting Edge Podcast Episode:

Pediatric Readiness

The 2026 season of the AAST Cutting Edge Podcast launched with new co-hosts Dr. Caroline Park and Dr. Susan Kartiko, who opened the year with discussion on pediatric readiness in adult trauma centers. Joined by pediatric surgery leader Dr. Barbara Gaines, the episode explores how trauma programs can better prepare for the critically ill and injured child who presents unexpectedly to their emergency department.

The conversation highlights the Pediatric Readiness Project and its evolution into a key component of trauma verification. Dr. Gaines emphasizes that pediatric readiness is fundamentally about identifying gaps — in equipment, medication dosing practices, imaging protocols, policies, and personnel — and developing targeted action plans to address them. Practical steps such as weighing children exclusively in kilograms, ensuring access to appropriately sized airway and resuscitation equipment, and appointing Pediatric Emergency Care Coordinators (PECs) are actionable starting points for trauma centers at any stage of implementation.

With the majority of children receiving emergency care in departments that see fewer than 10 pediatric patients per day, the episode underscores a critical truth: children will present to our trauma centers, and readiness is not optional. It is an essential component of delivering high-quality trauma care across the spectrum.

Missed an Issue?

If you missed the last issue or want to revisit past content, you can browse all previous editions on our archive page. Whether you're looking for policy updates, committee highlights, or educational content, it's all there.

The Cutting Edge Podcast

Prefer to listen on the go? The Cutting Edge Podcast brings AAST to life with engaging conversations, exclusive interviews, and behind-the-scenes stories from the world of trauma and acute care surgery.

Front Line Surgery: Mastering Military Trauma Care

Tune in to Front Line Surgery: Mastering Military Trauma Care, a podcast dedicated to military trauma care. Each episode features expert military surgeons sharing real-world cases and battlefield-ready strategies.