The Needle Tip: Current Management of Pediatric Hand Burns

Steven L. Moulton, MD, FACS, FAAP

Colorado Firefighter Endowed Chair for Burn and Trauma Care

Director, Trauma and Burn Services

Children’s Hospital Colorado

Professor of Surgery

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Children are curious by nature and learn about their world through tactile exploration with little comprehension of the dangers that surround them. Vigilant parents can recognize and anticipate some of these dangers; however, the pace of childhood development is often underappreciated. Toddlers can quickly wander away from a parent or caregiver to an unsafe setting where they will naturally touch and grasp things, and move from one object to another as they explore new territory. The dancing flames behind a hot, glass-fronted, gas fireplace1 or the convenient height of an open, hot oven door may attract them. Spinning treadmill belts are another curiosity and are the frequent cause of deep, full-thickness abrasions to the fingers and palm. Hot stovetops, clothing irons, and hair straighteners are other common causes of heat-contact types of pediatric hand burns. In addition, too often, a freshly brewed cup of coffee, a pot of boiling soup, or a hot frying pan is within a child’s reach, resulting in deep, painful, scald-type burn injuries involving the hand(s), and oftentimes, the arm(s), face, and/or torso too.

Although pediatric hand burns are extremely common and most heal on their own, caring for a child with burns to one or both of their hands is difficult for parents and is a distinct challenge for practitioners.2–5 There is the inherent pain associated with dressing changes, the need for diligent wound care and optimal positioning, temporary loss of use of one or both of their hands. (Some of our parents will drive eight or more hours for a proper dressing change at our burn center because Children’s Hospital Colorado is the only pediatric burn center in the Rocky Mountain region.) Another consideration is the fact that parents often feel guilt, remorse, and anxiety when they witness their child’s pain during a dressing change; we have a psychologist, who is dedicated to the burn team, to address these types of issues.

To minimize the adverse effects and sequelae associated with the outpatient management of pediatric hand burns, we use intranasal fentanyl to manage pain and a soft-casting technique to stabilize and protect a child’s burn-injured hand(s). These methods allow us to reduce the frequency of dressing changes and keep the pediatric hand in an optimal position for healing while enabling the child to play. These methods are anathema to traditional burn wound care, which involves daily or twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine.2, 4, 6–8 Frequent dressing changes, however, are both painful and disruptive to a healing wound, and a burn wound that is improperly splinted will heal in a contracted position, preventing full palmar or dorsal expansion and full mobility once it has healed.

Optimal healing occurs when a burn wound heals in a controlled and undisturbed environment. This is made possible by modern-day burn wound dressings that wick excessive moisture away from the burn wound, have anti-bacterial (and/or anti-fungal) qualities, and are therefore safe to leave undisturbed for up to one week.9 These dressings, in combination with the soft-casting of the burn-injured hand, maintain a stable, moist environment and limit disturbance of the wound bed, allowing optimal cell proliferation and burn wound closure. More importantly, soft casting allows healing to occur in a position of function. All tissues prefer to rest in a position of comfort, or the tissues’ resting length. The position of comfort after a palmar burn injury is a loosely fisted posture—a position that promotes contracture of the palm. During the acute phase of wound healing, positioning that supports skin healing in its lengthened position allows for maximal tissue length and decreases the risk of contracture formation.

Burn injuries to the palm are more common than to the dorsum side of a child’s hand. They are also more difficult to manage because of the dominant strength of the muscles that allow grip as compared to the strength of the more intricate extensor muscles. Thus, the optimal position for palmar burns is to maintain full tissue length by positioning the hand in full palmar expansion. This is a position of finger abduction, and radial abduction of the thumb and wrist extension. In this position, all of the arches of the hand are in their elongated position, and there is maximal lengthening of the skin of the palm. This position of full-palmar expansion is difficult to maintain using typical splinting techniques, especially when the splint is placed over the dressing of an active child.

Dressing Technique

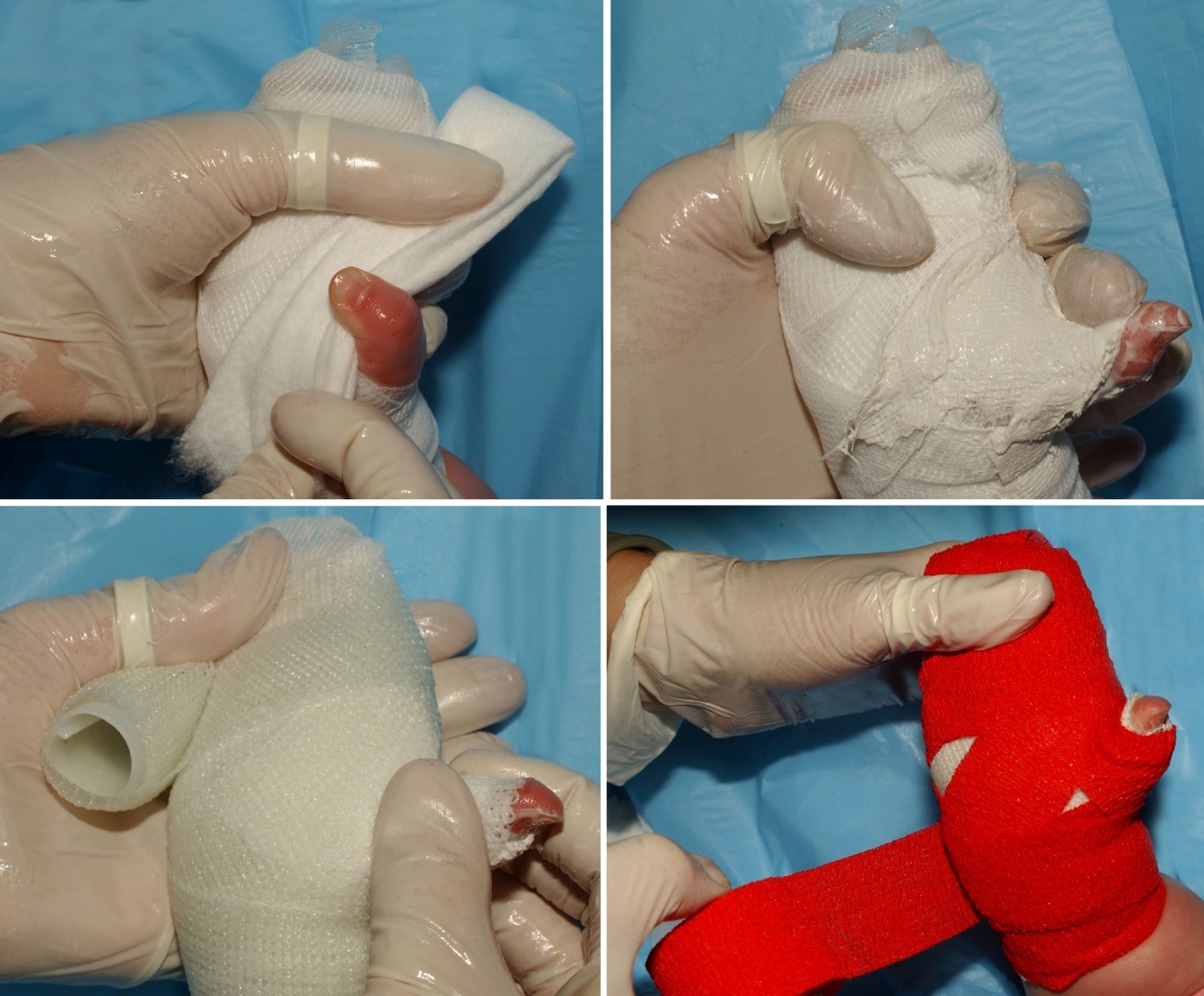

Children with burn-injured hands who are referred as outpatients to our burn center are assessed and premedicated with intranasal fentanyl (0.5–1.5 mcg/kg/dose) prior to removing their dressing(s). They are monitored with continuous pulse-oximetry, and if they are anxious, a ChildLife specialist is brought into the room to calm them, distract them, and allay their fears. The child’s dressings are unwrapped, and the burn wounds assessed. Flat blisters are left intact. Raised blisters are debrided around the perimeter with fine scissors so that the dressing will snuggly fit the contours of the child’s hand. The open burn wounds are then covered with gauze sponges soaked in a dilute hypochlorous acid solution (Vashe®, SteadMed®; Fort Worth, TX) for 3–10 minutes, depending on the amount of necrotic debris and slough present in/on the wound(s). This debris is gently wiped away from the open burn wounds and then the wounds are covered with strips of non-adherent gauze (AdapticTM, AcelityTM; San Antonio, TX) that is impregnated with triple antibiotic ointment (TAO [neomycin, 3.5 mg/g; bacitracin zinc, 400 units/g; and polymyxin B sulfate, 5000 units/g]). (See Figure 1.) This process requires the teamwork of a burn nurse and a pediatric occupational therapist. The nurse debrides the blisters, and the occupational therapist, who is accustomed to working with tiny squirming fingers, dresses the involved digits and surfaces of the hand. The dressed fingers and thumb are then circumferentially wrapped with one-inch rolled gauze. Two-inch rolled gauze is wrapped around all four fingers, the thumb, the hand, and the wrist (Figure 2). Then, two-inch cast padding is wrapped: (1) around the fingers and down the dorsum of the hand and wrist, (2) around the base of the thumb, and (3) circumferentially around the wrist to protect the underlying bony prominences. Next, two-inch plaster is placed over the dorsum of the fingers, down to the wrist, and around the base of the thumb to aid in positioning the fingers, thumb, palm, and wrist. Next, one-inch soft-cast tape (ScotchcastTM, 3MTM Company; St. Paul, MN) is wrapped around the fingers, hand, and thumb; this is followed by two-inch soft cast tape. Finally, a colorful, self-adherent wrap (CobanTM, 3MTM Company; St. Paul, MN) is wrapped around the soft cast tape to keep the dressing neat and tidy. Typically, each soft-cast dressing is changed on a weekly basis until the burn wounds have healed. After 7–10 days, triple-antibiotic ointment is switched to Nystatin ointment for fungal infection prophylaxis. Children who are placed in a soft-cast type dressing can ambulate and bear weight, but are restricted from participating in high-impact activities and bathing; the cast must be kept dry.

If a child has deep, partial thickness burns with open, weeping wounds and a moderate amount of swelling of the hand, we omit the cast and apply a soft dressing composed of AdapticTM with antibiotic ointment or Meptiel® AG (Molnlycke®; Oakville, Ontario), Kling, and Coban. This dressing is changed every 2–4 days until the burn wounds stop weeping and the swelling resolves. At that point, the open burn wounds are dressed in AdapticTM impregnated with Nystatin versus Mepitel® AG, and the child’s fingers and hand are soft-casted, as described above, for one week.

Skin Grafting

Pediatric hand burns that are clearly full thickness are excised and grafted within a few days of initial presentation. Burns with deep, partial thickness are serially dressed and a decision on whether to excise and skin graft the residual open burn wound(s) is usually made between 10–14 days post burn. Burns to the dorsum of the hand, fingers, and thumb are excised under 2.5x magnification with a Weck blade using a 0.004–0.006-inch guide. Hemostasis is obtained with Telfa® (AmericanTM Surgical Company; Salem, MA) or a similar nonadherent pad soaked in an epinephrine saline solution (30 mls of epinephrine [1,000 units/ml] in one liter of saline). A split-thickness skin graft is harvested from the ipsilateral thigh or buttock and glued down to the hemostatic, excised burn wounds using fibrin glue (Artiss®, Baxter Healthcare Corporation; Westlake Village, CA), then further secured with 6-0 plain gut suture. Burns to the palmar surfaces of the fingers, thumb, and palm are circumferentially incised with a #11 blade, and then tangentially excised with fine iris scissors. Full-thickness skin grafts are harvested from non-hair-bearing skin (ipsilateral wrist, antecubital fossa, lateral groin crease, hip thigh crease, or anterior abdominal wall) and secured with interrupted 6-0 chromic, followed by running 6-0 plain-gut sutures. The child’s fingers, thumb, and hand are immobilized using the soft-casting technique described above.

Summary

Pediatric hand burns have been shown to have a more significant impact on developmental growth than burns in other areas.10, 11 Soft casting with plaster reinforcement has many advantages. First, the integrity of the cast allows the child to play with few restrictions, yet is also difficult for a young child to remove. Second, the cast allows the injured extremity to heal in an optimal position. Third, it only requires weekly dressing changes in an outpatient setting. Weekly dressing changes reduce the number of long-distance trips to the burn clinic for patients in our large geographic catchment area. Fourth, the soft cast maintains a moist environment for the healing wound. We typically use an antibiotic ointment with an Adaptic® nonadherent dressing to provide moisture to the burn wound, and the soft cast helps retain some of that moisture. This minimizes adherence of the dressing to the wound and allows for easy removal, which is done by simply unwrapping the dressing.

Bibliography

- Wibbenmeyer, L., M.A. Gittelman, K. Kluesner, J. Liao, Y. Xing, I. Faraklas, W. Anyan,

- Gamero, S.L. Moulton, et al. A Multicenter Study of Preventable Contact Burns from Glass-Fronted, Gas Fireplaces. J Burn Care Res, 2015. 36(1): 240–245.

- Sheridan, R.L., M.J. Baryza, M.A. Pessina, et al., Acute Hand Burns in Children: Management and Long-Term Outcome Based on A 10-Year Experience with 698 Injured Hands. Ann Surg, 1999. 229(4): 558–64.

- Barret, J.P. and D.N. Herndon, Plantar Burns in Children: Epidemiology and Sequelae. Ann Plast Surg, 2004. 53(5): 462–4.

- Scott, J.R., B.A. Costa, N.S. Gibran, et al., Pediatric Palm Contact Burns: A Ten-Year Review. J Burn Care Res, 2008. 29(4): 614–8.

- Barret, J.P., M.H. Desai, and D.N. Herndon, The Isolated Burned Palm in Children: Epidemiology and Long-Term Sequelae. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2000. 105(3): 949–52.

- Sheridan, R.L., L. Petras, M. Lydon, et al., Once-Daily Wound Cleansing and Dressing Change: Efficacy and Cost. J Burn Care Rehabil, 1997. 18(2): 139–40.

- Peters, D.A. and C. Verchere, Healing at Home: Comparing Cohorts of Children with Medium-Sized Burns Treated as Outpatients with In-Hospital Applied Acticoat to Those Children Treated as Inpatients with Silver Sulfadiazine. J Burn Care Res, 2006. 27(2): 198–201.

- O'Brien, S.P. and D.A. Billmire, Prevention and Management of Outpatient Pediatric Burns. J Craniofac Surg, 2008. 19(4): 1034–9.

- Choi Y.M., C. Nederveld, M. Milan, K. Campbell, and S.L. Moulton. A Soft Casting Technique for Managing Pediatric Hand and Foot Burns. J Burn Care Res 2017 (in press).

- Palmieri, T.L., K. Nelson-Mooney, R.J. Kagan, et al., Impact of Hand Burns on Health-Related Quality of Life in Children Younger Than 5 Years. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2012. 73(3 Suppl 2): S197–204.

- Birchenough, S.A., T.J. Gampper, and R.F. Morgan, Special Considerations in the Management of Pediatric Upper Extremity and Hand Burns. J Craniofac Surg, 2008. 19(4): 933–41.

Figure 1. The blistered skin is sharply debrided and the open-burn wounds are covered with nonadherent gauze that is impregnated with triple-antibiotic ointment. This is followed by wrapping with one-inch rolled gauze, if the fingers are involved, then two-inch gauze.

Figure 2. Soft-cotton cast pad is applied to protect bony prominences of the wrist and the base of the thumb. This is followed by plaster, which will reinforce the soft-cast material and keep the palm, thumb, and wrist in full expansion. An elastic outer layer keeps the underlying dressing materials neat and tidy.